A perennial and fairly meaningless question that is often asked is ‘what are the origins of Crossrail?’ It inevitably depends on how far you want to go back in time but one contender could be the groundbreaking scheme developed in the 1930s to electrify the Great Eastern (GE) Main Line from Liverpool Street to Shenfield with the intention of providing an intensive electric service to many suburbs of East London.

The 1930s were in the middle of the era where the railways of Britain were in the hands of the ‘Big Four’ privately owned railway companies. In 1923 the Great Eastern main line became part of the LNER (London & North Eastern Railway). It was, and is, the main line to Chelmsford, Ipswich and Norwich.

Why Electrify as far as Shenfield?

Shenfield was the logical choice for the eastern end of a suburban electrification scheme. The major centre of Romford would be included and beyond were the towns of Harold Wood and Brentwood. Shenfield was, and is, effectively a district within the urban sprawl of Brentwood. Beyond the outer boundary of Brentwood there was widespread countryside – too far from London to justify an intensive urban railway and also too distant to significantly alter the existing land use with a stopping service.

More to the point, the Great Eastern main line was already four-tracked as far as Shenfield with the lines beyond Shenfield being two-track. The branch to Southend Victoria turned off the main line just north of Shenfield, making Shenfield a notable railway junction and the location where passenger density reduced.

Part of Something Bigger

Shenfield Electrification was really part of a larger comprehensive scheme for East London involving main line electrification, resignalling, new rolling stock, a new railway depot and closing a short section of railway. The larger scheme also involved building new tube tunnels and transferring part of the existing network in North East London to the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) so that they could extend the Central London line into the North East suburbs of London (and beyond). This in turn meant that the Central London line required new rolling stock and new depots.

The Central London line Factor in the West

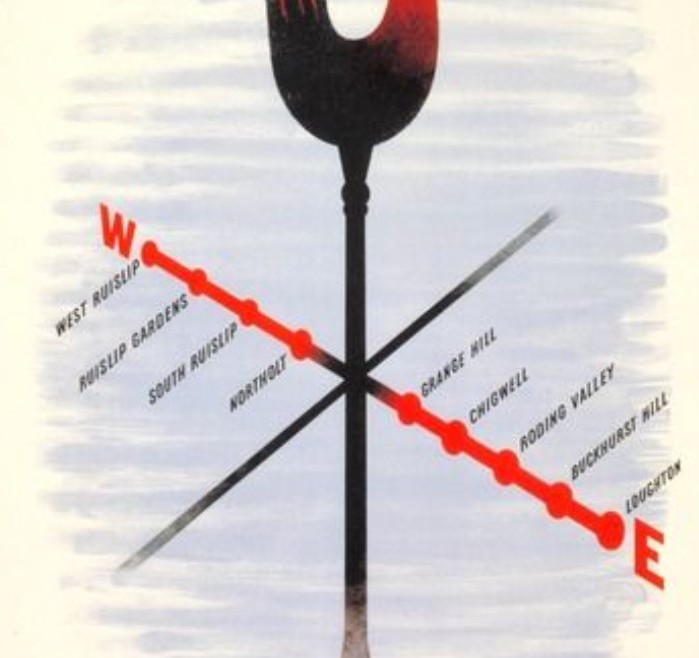

Additionally, an extension of the Central London line to the west of London by means of a separate branch from Wood Lane to West Ruislip (later to Denham) was proposed as an integral part of the scheme.

The scheme’s purpose in West London was two-fold. One was to enable a large depot to be built at Ruislip, in order to supplement the proposed eastern tube depot at Hainault which could not, on its own, provide enough trains for the whole line. Clearly the existing Central London line depot located at Wood Lane would be totally inadequate to serve the considerable extensions. Furthermore, it was limited to 6-car trains rather than 8-car trains which would be provided as part of the Central London line enhancement.

A second reason for the western extension, which was to be built by the Great Western Railway, was to provide two balances:

Operationally, so that trains from the east had somewhere else useful to run to on the west side of London, in order to provide a more balanced service over the whole line making better use of line and train capacities.

Financially, to help develop new suburbs which were expected to generate more profitable off-peak travel than the eastern suburbs.

A Lengthened and Renamed Central London line

If things went as planned the Central London line would be transformed from a relatively short simple Underground line between Ealing Broadway and Liverpool Street totalling just 11 miles into a major Underground line totalling approximately 57 route miles.

To give some idea of just how extensive the Central line would be we have shown in a map below the extent of the planned and authorised Central line. This includes a short section from West Ruislip to Denham which was never built. By comparison, the map also shows the extent of Crossrail at the time of it being authorised which is shown in purple and lime green. The originally authorised Crossrail scheme appears to be more extensive but not by any considerable extent. Maidenhead is further from Paddington in terms of route miles than Liverpool Street is from Ongar but by less than one mile. West Ruislip is just over 13½ miles from Lancaster Gate (close to Paddington) which is almost exactly two-thirds of the distance of Shenfield from Paddington.

It was clear that ‘Central London’ would become a complete misnomer for the name of this geographically spread railway. A consequence of all these plans was that during this period the name was simplified, to become the Central line.

A Tube to Bucks and Essex

The Central line would have two branches, both owned by the GWR, on the west side of London, with the existing line to Ealing Broadway, and the new route extending via the length of Middlesex into Buckinghamshire at Denham. On the eastern side, the main route would extend way beyond the London County Council border, and end at Ongar only 10 miles from the heart of Essex (Chelmsford). A large loop (the Fairlop/Hainault line), partially converted from an existing LNER line and partially in new tunnels under Eastern Avenue, would be wholly within the 1930s Essex.

The planned extension into 1930s Essex ultimately helped redefine where the outer edge of London lay and, once redefined, did much to determine where it would be for evermore.

A Complex and Many-Faceted Scheme

The outcome of these consolidated proposals meant that a scheme primarily designed and initiated in order to improve transport in East and North East London became dependent on developments many miles away.

As if all that wasn’t enough, due to the extra traffic and longer trains anticipated, existing Central London line platforms would be lengthened to take eight carriages and this involved lengthening the platforms at all 14 underground stations between Liverpool Street and Shepherds Bush. There was also to be an expansion of passenger-handling capacity at some stations, such as at Chancery Lane and St. Paul’s.

Nearly an early Crossrail equivalent?

Under normal circumstances such extensive station works would be considered a major project, not just a small component in a much bigger project. So, the combination of extending and upgrading the Central London line, and the joint involvement of main line railways both west and east of London, was really a large-scale Crossrail-style project in its own right, albeit with tube-sized not main-line sized trains.

New space-efficient tube trains with under-floor equipment were trialled by LPTB in 1935. These meant that, for the first time in multiple-unit tube stock, passengers had access to all of the carriages with the exception of the driving cabs. These trains were originally intended for the Central London line. When the production version was introduced, it was regarded as a significant advance in tube train design and the latest thing in modernity. If these trains had been introduced on the Central line, the revitalised and hugely extended tube line would have exhibited remarkable parallels (literally and figuratively) with today’s Elizabeth line.

However, for various complex reasons, the plans changed, and the production version of the new tube trains (the 1938 tube stock) saw use in central London on all London Transport tube lines except for the Central line, which made do with ‘standard’ tube stock shuffled mainly from the Bakerloo and Morden-Edgware (subsequently renamed ‘Northern’) lines. The result may have been more beneficial for Londoners overall but the opportunity to present London with a modern-looking and extended tube line was missed.

The Level Crossings Issue

A further element of the combined scheme was the requirement to close various highway level crossings on existing LNER tracks as it was deemed unacceptable to have level crossings with frequent tube services.

Apart from any policy considerations, it was clear that the potential intensive service level would make most level crossings unworkable for road traffic. Whilst this might sound a minor issue, it was actually a major challenge. Most of the crossings involved were located in suburbs of London which had already seen substantial 1930s development. It was also a task more appropriate for a highway authority to implement rather than one to be left to railway contractors as part of a bigger construction project. For this reason, at the time this was considered to be a third element of the scheme to complement Shenfield electrification and Central line extension.

The Scheme Almost without a Name

Much has been written about the Shenfield Electrification project. Much has also been written about the enhancement of the Central line in the 1940s including the newly built tunnels under Eastern Avenue being temporarily used as a factory for war output. However, rather less has been written about how absolutely interdependent these schemes were. One reason for that may be that the scheme never really had a commonly-used name encompassing all the features involved. The scheme did appear to have a formal name of the Central Line Extensions and Shenfield Electrification Scheme but this seems to have been rarely used. For convenience and brevity we will sometimes refer to the schemes as the ‘combined scheme’.

If the scheme gets mentioned by name at all, it tends to either get described by its component parts or by referring to it as part of the 1935-40 New Works Programme. The latter was an all-encompassing package of planned measures, most of which were implemented (although much was completed after World War II). In the case of the Northern Heights scheme within the New Works Programme, the less rewarding parts were abandoned post-war, even though parts of those had been close to completion pre-war.

Perceived Importance

It probably reflects on the potential benefits of the schemes (Central line extensions and Shenfield Electrification) that these were completed when other New Works Programme component schemes floundered. After World War II a shortage of steel, money and, possibly more important still, labour desperately needed to build new housing stock caused unfinished schemes to be delayed or abandoned. However, it is noticeable how considerable priority was given to completing both schemes although the post-war Labour Cabinet did debate on whether to stop Central line electrification at Loughton or at the new LCC housing estate at Debden.

The importance given to Shenfield Electrification and Central line works immediately after World War II is in marked contrast with, for example, the proposed extension of the Bakerloo line from Elephant & Castle to Camberwell which came to nothing despite a clear need at the time and previously. This latter scheme was considered important in order to increase capacity on the Bakerloo line by means of enabling more trains to be turned around at its southern end by providing a three-platform terminus.

The Contrasting Failure to Prioritise Bakerloo line Problems

Nowadays it is hard to believe that the Bakerloo line was the most overcrowded tube line but by 1940 it had two northern branches – one all the way from Baker Street to Watford Junction via Harrow & Wealdstone and one (a New Works Programme scheme) from Baker Street to Stanmore. The newly acquired Stanmore branch was found to have just too many passengers for the line to operate efficiently and give users a reasonably satisfactory journey.

Along with the proposed Bakerloo branch to Stanmore, there was a pre-war plan to extend existing Bakerloo line platforms to cater for 8-car trains. This turned out to be challenging due to the line gradients and curves in the vicinity of underground stations. This, combined with costs, meant that eventually platforms were only extended to accommodate one extra carriage. It was 1946 before they were utilised.

The failure to implement fully the scheme to increase capacity is one which created significant problems until 1979 when the first stage of the Jubilee line was opened and took over the Stanmore branch. However, use of 1938 stock with its higher passenger capacity than the previous ‘standard’ stock gave some relief to Bakerloo crowding.

The planners and the government of the day were probably not remiss when it came to abandoning the Bakerloo line extension which would have enabled a higher frequency of service and hence greater capacity due to the proposed three-platform terminus at Camberwell. Faced with practical issues involving shortage of many things, including money, something had to give. Schemes had to be prioritised and improvements in East London were considered an even higher priority.

Post-War Priorities Within the Scheme

After the Second World War, with Cabinet support, authorisation was made for the combined scheme to proceed with all possible haste – shortages of labour and materials notwithstanding.

The eastern side of London appeared to be treated with more urgency than the western side. However, this may have been a simple case of construction priorities due to the considerable amount of work required in East London.

For example, just to remove the concrete floor from the recently-built Central line tunnels used as an armaments factory during the war was reported to have taken eight months, as the concrete was considerably harder than anticipated and only once that was done could the tunnels be fitted out to be used as a railway. Also, only when Central line trains reached Leytonstone (in May 1947) and enabled the through LNER service to be withdrawn, could the LNER get on with reconstruction and reorganisation of the main lines between Stratford and Liverpool Street.

Nevertheless, the western extension, now curtailed back to West Ruislip, could not be ignored because the rolling stock from the Ruislip depot would be vital for providing the extended service over the entire line. The depot had to be functioning and it had to be linked to the existing Central line. Whether a public service was initially provided on the new western extension or not was less critical.

In the event, both the eastern as far as Loughton and the western extension to Ruislip opened on the same date although staged progress had been made prior to then. However, many stations on the western extension were reported to have been in far from a finished state on their opening day.

The Steam Age Forerunner of Crossrail’s Shenfield Branch

The railway line out of Liverpool Street Station to Romford and beyond has been exceptionally busy for at least the past hundred years. Whilst built much earlier, it really started to become intensive around the beginning of the 20th century with housing developments in Forest Gate and Ilford. From then development moved outward from the centre of London along the route of The High Road (the former Roman Road) between London and Colchester and with that came more demand still for trains on the London-Shenfield route.

In steam days the service on the London-Shenfield line was reputed to be the most intensively run steam-operated service in the world. There are various accounts of the slick operation necessary to carry the number of passengers using it. In general, they report wonder at how such an intensive service could have been operated with carriages pulled by steam engines. Somewhat perversely, the LNER, judging it could not afford to electrify, seemed to have a policy of aiming to increase further the intensity of trains run – as if to show their critics what could be achieved without electrification.

The reality was that LNER was thinking too much with a view to making a steady, if small, profit rather than a visionary approach that could transform the company. It wanted to electrify but it was a company whose first obligation was to its shareholders and, however hard they looked at the figures, they could not show a predicted return of 5% early on, which at the time was the generally accepted requirement before one could rationally invest in a project – and raise finance from new share issues.

Failure to Attract Off-Peak Traffic

One of the fundamental problems with getting a good return on what seemed like an obviously good economic investment was the minimal off-peak traffic. And, worse still, the peak periods were heavily peaked. One cannot blame the LNER for not trying to attract off-peak traffic as the publicity below clearly shows that they did try. Despite the efforts that they made, they were clearly unsuccessful.

The Problem of Financially Justifying Electrification

This was put very bluntly in a December 1933 report submitted to the Ministry of Transport using wording and sentiment that probably would not be so blatantly used today.

One result of the traffic being mainly working class in character is that it travels for business purposes only. This creates heavy traffic loads at the peak hours and far too light traffic loads at slack hours, as the population has neither the resources nor the aptitude to seek its pleasures and shopping other than locally. On the Upminster line some 40 per cent and on the Shenfield line some 35 per cent of the total daily traffic in either direction is carried within a single hour. Elsewhere on the Underground System of Railways the highest percentage of movement for a single hour is 26 per cent.

Extract from Report on The Traffic Problem in the North-East Sector of London 30/12/33

That paragraph probably needs analysing in some detail taking into account the language and social conditions of the day. “Business purposes” clearly meant ‘commuting’ but that term was not used in those days as it originated in America to describe someone with a season ticket (a ‘commuted’ fare) and the term was not in common use in Britain until the 1960s. An alternative way of describing the situation at the time would be to refer to the inhabitants as an ‘industrial population’.

The term “slack hours” was a common one in those days but is not much in use now. ‘Off-peak’ is now favoured as the ‘slack hours’ are often anything but slack.

35% of all traffic in either direction being in a single peak hour might not sound too bad but further analysis shows just how terribly peaked the traffic is. That means that the rest of the railway operating day accounts for the remaining 65% of traffic. The Liverpool Street lines then ran a 20 hour ‘traffic’ day – there were a few night services as well. That means that the passenger volume in an average ‘slack’ hour was only 3-4% of the daily passengers, and just one-tenth of the crowded peak hour.

The “business purposes” (commuting) importance of the NE London-North Woolwich corridor should be noted as should the radial routes from Liverpool Street. The former is highlighted by the design of the diagrammatic map displayed above (“Day Return Tickets at Single Fares”) showing a strategic travel corridor SE to the river. However, direct trains to the Docks and Thameside industries via Stratford also came from multiple suburban lines in North and North East London. Omitted from the LNER map also is a busy link via Stratford from Victoria Park interchange on North London railway owned by the London Midland and Scottish Railway (LMSR).

Without widespread electrification in NE London, it was probably not worth thinking of electrifying the Stratford-North Woolwich line as many local trains would remain steam-hauled. North Woolwich electrification wasn’t mentioned in LNER proposals of the period. Basically, if one were to electrify anywhere in East London then only Liverpool St-Shenfield made sense as an initial scheme.

Prudently, the official writing the earlier quoted paragraph did not mention either the situation at other railway companies nearby or the comparable South Eastern suburban lines of the Southern Railway (SR). The latter suburban lines had a similar peak demand, including Woolwich Arsenal as a destination, and limited travel during slack hours, yet were largely electrified in the mid-1920s. They also had a significant number of lines operated using colour-light signalling, which aided greater operating efficiency.

Lessons to be learnt from LTSR/District Southend Services?

Outside peak times, the LNER had two main options to stimulate additional travel, other than the obvious ones of more frequent services or strong marketing. One was to offer through trains to key ‘attractor’ destinations,

the other was to offer easy interchange to frequent services on lines which reached those destinations. It is instructive to see what was happening on the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway (LTSR, today’s c2c).

Heading away from London on the LNER and LTSR/Midland corridors into Essex, a key destination opportunity was Southend, and both main line companies strove to grow that off-peak market, with occasional through trains to Southend Victoria (LNER) and Southend Central (LTSR) from their suburban lines in Middlesex, Essex, and North and North East London. Towards the capital, the key destination was the heart of Central London beyond the City termini, particularly the West End, and this was a large enough destination to justify considerable investment in through services or interchanges.

A pre-WW2 example of an alternative to providing a good interchange which may have been in the minds of decision-makers, could be the joint running of trains from 1910 between the LTSR and the District Railway across Central London. This was intended to take advantage of spare off-peak capacity with attractive destinations in each direction. This was a through service from Ealing Broadway via Central London to Southend, and vice-versa, hauled by District electric locos to Barking and then a change to steam to Southend.

Conceptually the Ealing Broadway – Southend service was a bit like today’s Crossrail. However the initial service was only three through trains daily, enough for a day journey to the seaside and a shopping expedition or an evening in London’s theatreland but not enough to stimulate a strong travel volume.

The Midland Railway (the LTSR owner from 1913) had a medium-term plan pre-WW1 to electrify to Southend, which would have provided strong stimulus for more through electric services. This never reached Southend under Midland ownership but, unlike the LNER, they did make significant progress when it came to electrification.

A Neighbour shows up the LNER

If early South Eastern electrification in the 1920s represented a comparable operator’s commentary on LNER’s shortcomings, it must have been even more galling for LNER’s own passengers to subsequently see the closely neighbouring, indeed parallel railway, the LMSR, investing in its own lines in the early 1930s.

When the London, Midland and Scottish Railway took over the Midland Railway in 1923 as one of the ‘big four’ companies, they declined to electrify the LTSR all the way, and instead focused on four-tracking and electrification of its stopping services east of Barking. This enabled the extension of UERL District Railway services to Upminster in 1933, to serve the new large-scale LCC Becontree housing estate and expanded industries along the north side of the River Thames.

However it was a LMSR-funded project, so pointedly showed up the LNER steam services, as one main line to another! A little later, the through Ealing-Southend trains were reduced (in 1938), and ceased in 1939.

The new Becontree LCC estates were also close to the LNER Shenfield services. On the LNER 1932 off-peak map on the back page of the Winter 1932-33 LNER suburban timetable, shown above (“Day Return Tickets at Single Fares”), Chadwell Heath station is labelled as ‘Chadwell Heath for Becontree’. This appears to be the only acknowledgement by the LNER of the existence of this massive new housing estate so, presentationally, it would puzzle residents and local councils why the LNER was not upgrading or investing in any significant improvements, even if not electrification.

Southern Contrasts

Based on a comparison between LNER and progress made by near neighbours, it is difficult to understand just how remiss the LNER was in failing to electrify at least some of its suburban services by the time of the previously quoted report. Rather than continue to dwell on the failings of LNER in East London, a comparison with how Southern Railway progressed with electrification and its wider London commuting development in the years since its creation in 1923 perhaps illustrates a clearer picture of just how far behind LNER was with what could have been achieved.

The Southern Railway already had an excellent starting point with the pre-WW1 suburban electrifications authorised on the LSWR (London & South Western Railway) from Waterloo, and LBSCR (London Brighton & South Coast Railway) from Victoria and London Bridge. Their networks were well positioned for peak and off-peak travel, with access both to the West End and the City, by tube and the sub-surface lines. LBSCR’s ‘Elevated Electric’ had even been promoted on Underground maps and other marketing pre-WW1.

The South Eastern sector (formerly the South Eastern & Chatham Railway) had not been electrified and historically its parent company, LNER-like, had struggled to finance improvements. However the SR wasted no time from its inception in implementing a massive electrification programme, including conversion of the LBSCR overhead electrification system to a standardised third-rail scheme as already on the LSWR and also expanded to the SECR.

Meanwhile, LNER had no lines whatsoever in the London area that were electrified despite their suburban services being an obvious candidate for an electrification scheme. None of the lines from Liverpool Street had colour light signalling although a slow start was made in 1935 when some sections of suburban railway, not on the route to Shenfield, had semaphore signals replaced with colour light ones.

‘Southern Electric’

By 1926 most of the SR’s three suburban networks were electrified and more schemes were under way. Electrification had reached beyond the suburban area to reach Dorking and Guildford. The rest of the decade was spent concentrating on filling in gaps in the existing suburban network. By 1930 the lines to Gravesend, Windsor and even the lightly used Wimbledon – West Croydon line had been electrified.

The early 1930s saw Southern electrification efforts concentrated on extending ‘Southern Electric’ to Brighton, Worthing and much of the South Coast (to Portsmouth by 1937), and with outer suburban services established for the intervening communities. As the Southern Railway was not one for half-measures, this included resignalling with colour light signalling wherever appropriate – all the way from Purley to Brighton by 1933, where the first electric train in public service ran from London to Brighton on 1st January 1933.

There was large-scale promotion of new housing and living opportunities in the same style as ‘Metroland’, with similar ‘Southern Electric’ marketing books and brochures. The South Eastern network, comparable in travel habits to the former Great Eastern lines, had been electrified as far as Sevenoaks by 1935, and to Gillingham (Kent) and Maidstone by 1939.

Southern’s ‘Electroland’

SR was keen to promote its investment and to stimulate more travel and more dormitory housing. There was an equivalent brochure to ‘Metroland’ – Country Homes (with various titles) – and visions of quality life on their improved railway network. Simultaneously the South Coast towns were promoted through marketing of longer distance electric services. Some examples are shown below.

Not entirely surprisingly, by way of contrast, LNER failed to produce any suburban marketing – although they might have felt they had too many passengers already for a steam age. We’re unsure what any ‘Live in Essex’ slogan might have stimulated.

A short-sighted LNER Board?

The reasons for this variance between the LNER and other main line companies are numerous and complex, but we would suggest a simple comparison is made between the LNER’s concern for day-to-day finances versus the Southern Railway’s Sir Herbert Walker’s vision to maximise line capacity involving all means, and the SR’s better financial base.

Given the short-term thinking and lack of access to capital, it is no wonder LNER couldn’t show how an investment in electrification would make a decent profit. To them it would seem to be a much better financial strategy to make do with what one had knowing in particular that one’s peak-hour travellers had very little choice and were a captive market rather than pursue a large investment in equipment that, in the prevailing travel mood, was only sensibly utilised for a couple of hours for six days of the week.

Lack of Suburban Development in Early 20th Century

When looking at suburban expansion in East London in early decades of the twentieth century, a slightly surprising contrast emerges. Heading more east than north, there was little development away from the route of The High Road and the railway to Romford. The line had no real rival nearby so much of East London was dependent on it. By 1932 the line was four tracked all the way to Shenfield leaving one pair of those tracks available for suburban use.

Eventually, the surrounding land which had been dominated by market gardening made way to urbanisation. What is surprising though is how the Fairlop loop (to become the Central line’s Hainault loop) failed to develop the expected population growth that the railway had relied on when extending to these parts. One possible reason for the failure to trigger a housing growth could be the desultory frequency which may have been accentuated by poor connections. To this day the Hainault loop is relatively lightly used and this cannot be entirely explained by the Green Belt.

The LNER’s failure to promote potential suburbs has to be one reason. Another might be the City of London’s 1930s interest in promoting a new City airport on Fairlop Plain – this was approved by a public inquiry in 1935 and was intended to open in 1942. That area subsequently became part of the Green Belt after a period as an RAF fighter station.

One area where there was considerable development was around Leyton and Leytonstone, which extended to a greater or lesser extent all the way to Loughton. This would have been centred around the railway line from Ongar, Epping and Loughton, whose trains went to the Fenchurch Street terminus as well as Liverpool Street.

Eastern Avenue in the 1930s

Eventually the pressures of the 1930s meant that housing spread further onto Essex fields. Much of this was centred around a 1920s-built arterial bypass road called Eastern Avenue, numbered the A106 in the 1920s (it’s now the A12). It mostly paralleled the existing built-up area based on The High Road and the Liverpool Street – Shenfield line, and created a new corridor from Leytonstone through Wanstead, Gants Hill, Newbury Park and Little Heath (north of Chadwell Heath). It then passed north and north east of Romford, to rejoin the A12 at the point where a new Southend Arterial Road began (the A127).

It wasn’t very far away (about a mile distant) from The High Road, meaning the effect was to bring additional passengers into the catchment area of the Shenfield line and increase intensity on the line rather than spread the load to other areas.

It is clear from what subsequently transpired that the developments around Eastern Avenue and their lack of direct rail services were of great interest to the Underground Group and then the newly-created LTPB who wasted no time in looking for potential solutions.

The Causes of the Demand for Travel

As mentioned earlier, travel in East London was mostly for work purposes. There were really two main areas with employment opportunities. One was central London. The other was the vicinity of the north bank of the Thames. A dominant source of employment was the Docks, while their close proximity to the Thames spawned numerous other industries.

The ability to unload raw materials made the surrounding area attractive to industry and warehousing. The Thames, being both a source of water and a place to dispose of it once used, also attracted manufacturing industry, for example sugar refining and syrup production. The combination of the two river features proved alluring to other businesses with a significant likelihood of causing effluents, which in turn made the locality less attractive for residential use. Hence a desire by some to live away from the area and possibly travel considerable distances to and from work.

The reality was that London as a whole was a major manufacturing centre, with extensive industries throughout inner London and along the length of the Thames and Lea riversides (and part of the Wandle), and with the Docks being a further stimulus for industries to locate nearby. Ford continued that heritage at Dagenham, while there was also intensive employment for East Londoners at the Royal Arsenal munitions factory at Woolwich and its offshoots (e.g. at Silvertown).

Central London based employment should not be thought of as just ‘the City’. The West End had become a large employment zone since 1900, while Westminster was the centre of Government.

Not relevant to Shenfield electrification but important when looking at the western extension of the Central line are locations such as Park Royal and Greenford that had sprung up as industrial centres during World War I. These locations, and others further down the GWR main line, were subsequently stimulated by rail and road access which had previously been missing or underdeveloped.

East London Travel in the 1930s

By changing at Stratford, Eastenders and East Londoners (i.e. those east of Bromley-by-Bow/Stratford) could make their way towards the Docks and other riverside industries. Their journey could continue from Stratford by either changing trains (some trains went within the PLA Docks area), or by using the then extensive East London tram network. Coborn Road, Leyton, Maryland and Manor Park were also rail/tram interchanges to reach various Dock gates and the local industries.

In many ways the comprehensive transport network that enabled workers to reach their places of employment would be considered exemplary. However, for many people, the bulk of the journey, distance-wise, largely relied on the intensively-worked, steam-operated trains that shuttled back-and-forth on the Liverpool St – Shenfield and Loughton routes.

A Railway Needing Change

Whilst the focus here is on the line from Liverpool Street to Shenfield, this was only one service that called at Stratford station. The range of travel origins to the Docks and riverside industry zones has already been highlighted, with through trains from both Central London and North and North East London, and they partly used the same London commuter tracks which were also used by Ongar and Loughton line trains. Further operational complexity existed with the presence of direct commuter trains to Fenchurch Street from the Ongar and Loughton line, which crossed the entire group of main lines in and out of Liverpool Street! This was a railway network in need of major operational reorganisation and the benefits of such a reorganisation would be felt over a large area.

Proposals to Improve Matters

The government in the 1930s was well aware of the importance of providing a decent railway service in East London. This had been highlighted by two major public inquiries by the London & Home Counties Traffic Advisory Committee in the mid-1920s, focused on East London and North-East London. Unfortunately, little had been done to address the basics, though there were plans which overlapped.

By now the LNER was one of the ‘big four’. They had proposed an electrification scheme at 1500V DC which would electrify much of the GE suburban network including to Shenfield, and the Ongar, Loughton and Fairlop Loop lines. A separate proposal was made by the Underground Group (still then a private company) to supposedly complement the LNER scheme and provide passenger relief to the LNER lines. In practice it competed with the LNER scheme.

In the above image, the base map shows urban development in 1923 which preceded the construction of Eastern Avenue. There are also 6, 9, 12 and 17 mile rings from Charing Cross and also M25 shown for modern-day comparison.

The Underground Group proposed a Central London line tube extension from Liverpool Street to Stratford Broadway (note: Broadway, not the main line station), which would then continue under Leytonstone High Street and along Eastern Avenue. The intended terminus was a small village called Little Heath which in those days was not yet part of the general urban sprawl.

Today, these plans were largely forgotten about. A critical weakness of them was their explicit competitiveness resulting in missed interchange opportunities and a poor commercial case. In fact, interchange opportunities were almost non-existent and even at Newbury Park it is not clear if there was any intention to provide interchange with the LNER station there (now part of the Central line).

OS map of around 1935 (w/ some later revisions included) showing Eastern Avenue, which is shown thicker than other roads, towards the top of the map. Little Heath is towards the top about two-thirds of the way across.

The Original Plans are Abandoned

A Central London line station located beneath Stratford Broadway wasn’t going to provide any interchange with the main line station at Stratford. Not only would there have been at least a 300m walk, there was the fact that exiting the underground platform in Broadway would necessitate not only reaching surface level but then climbing further stairs at the main line station to reach the elevated platforms.

The proposed Underground extension was comparable with the Piccadilly Line extension northwards from Finsbury Park, which had just opened under the roads to central Wood Green and into new development territory in outer North London, paralleling but not integrated with the LNER Great Northern network. The Piccadilly tube was an alternative railway (in areas where passengers had a choice of local stations), rather than a network offering good interchanges between operators. In the case of East London, Liverpool Street would have continued to handle all the transfer flows between the LNER and the Underground.

It is probable that neither the East nor North East London schemes could be justified by their partly duplicated demands on capital investment, in a part of London where off-peak travel was so discouraging, and where even the finally approved scheme needed other, more profitable schemes to go ahead, to provide sufficient assurance of an acceptable rate of return.

A Basis for a Realistic Scheme

The formation of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB, London Transport, LT) in 1933 and particularly the Standing Joint Committee of LT and the main line railways, was a means to force joint railway planning to take place, in return for which the Government would be willing to provide financial backing for an integrated set of railway development plans.

The Standing Joint Committee brought together the competitive proposals by the LNER and the Underground Group for schemes to relieve travelling conditions in East and North East London.

In actuality, the December 1933 report prepared the political ground for the works that were finally authorised for the 1935-40 New Works Programme. Subsequently, by putting heads together both the LPTB and LNER eventually saw ways to merge the different schemes and make a stronger combined proposal.

A Revision is Needed

One can see the problems with the original schemes. There was limited capacity at the London termini so there just would not be the enabled service expansion that would permit the LNER scheme to pay its way. From the LNER’s viewpoint, if it divested the Ongar, Loughton and Fairlop Loop lines to London Transport then its immediate capital costs would go down, yet there was a substantial probability of passenger numbers after electrification being around the same, or even higher, despite the loss of some passenger lines.

After 15 years, the amortised charges of the Central line’s eastern extensions would also would be loaded onto LNER shareholdings, in proportion to the share of LNER trackage operated over by the LPTB, but by then the passenger traffic should have grown enough to pay for the new works. Such a scheme must have appeared far more profitable to the LNER than the original one proposed.

The possibility also must have occurred to LNER that, if the Great Eastern Main Line were already electrified on the main lines (the former ‘through’ lines) as far as Gidea Park, as planned, there would be the opportunity to build on that in future and possibly extend towards Southend Victoria and Chelmsford. Both were beyond the London region’s shared revenue ‘Pool’, but not by far. Outer suburban electrification would be expected to be considerably cheaper than that in the urban areas on a cost per mile basis due to less need for bridge reconstruction and, furthermore, could take advantage of lines already electrified in the urban area.

One could argue that the fledgling London Transport (formally the LPTB, of course) was still finding its way as to its real purpose during this period. As a public corporation as well as a Pool member, its role should be one of finding the best transport solutions regardless of which company or public body implemented them. The previous competitive stance needed to be modified to enable co-operation to produce a better solution that could realistically be implemented.

Eventually, a revised scheme was developed in conjunction with London Transport to extend the Central London line into suburban development areas. This was expected to show adequate investment returns to the ‘London Passenger Transport Pool’ (the pooled income from LT and the four main line companies) from the resulting travel growth – here considering the LPTB and LNER revenues – once the eastern areas had been developed and balancing suburban areas had emerged in the west.

A consequence of the ‘Pool’ scheme was that companies would be less concerned with protecting ‘their’ revenue. Rather than fighting for their share of the cake the emphasis was on producing a bigger cake so everyone had a larger slice. This became significant at Stratford where easy interchange between the LNER and Central line was regarded as “essential”.

A Stratford interchange would make journeys to central London and beyond from the Ilford, Romford and Shenfield corridor more attractive and, it was hoped, more generally lead to the much-desired gains in off-peak travel, by offering a simple, high-quality cross-platform interchange with trains direct to the West End. So a Stratford Interchange scheme was included in the 1935-40 New Works Programme, which along with many other New Works was approved through Parliamentary Acts.

1935-40 New Works Programme (and subsequent Acts)

As well as providing the railways (LPTB, LNER and the GWR) with a trajectory for growth, there were wider public policy reasons for this agreed programme. In order to stimulate the economy during a time of financial depression, and to provide employment opportunities, the Government in the 1930s was prepared to underwrite advance funding for railway improvements that benefitted the economy in general but weren’t immediately profitable on their own.

It raised £40m (now around £40 billion) in a government-backed shares offer, to fund the 1935-40 New Works, with the shares to be transferred to LPTB and the railway companies after a 15-year period of investment and consequential area development. This was hoped to be long enough for the shares to earn their long-term worth.

The above map shows the 1935-40 New Works Programme as finally approved and implemented. Existing lines to be electrified are shown in lime green and consists of:

Liverpool St – Shenfield (1500V DC overhead)

Most of the Fairlop loop (630V DC standard LT fourth rail)

the Ongar line as far as Epping (most of it off the map, 630V DC standard LT fourth rail)

Fenchurch St – Stratford (1500V DC overhead)

There is a flyover to swap the pairs of lines which is just visible to the west of Ilford which will be explained in a later article.

The new Central line tunnels are show as red tramlines and consist of:

New tunnels from Liverpool St (extending the existing Central line) to Stratford where they surface at Stratford station.

New tunnels between Stratford station and Leyton station along a route which consists of an awkward ‘S’ bend to join these locations.

New tunnels under Eastern Avenue from Leytonstone to Newbury Park featuring a substantial curve south of Newbury Park in order to change from an West-East alignment to a South-North one in order to take over services on the Fairlop (now the Hainault) loop.

More Detail

This article provides a background of the planning rationale for the Shenfield Electrification Scheme and related schemes that this electrification depended on. In the next article we will look at in detail as to what this actually meant on the ground, what was involved in implementing the scheme, and how the close the eventual result matched the pre-war plans.

The post The Shenfield Electrification Scheme: Background appeared first on London Reconnections.