We just looked at TfL’s efforts to expand step-free access on its network. Level access is definitively patchy on TfL’s network, and the same goes for the Network Rail. Whilst the London Underground is famous for reminding passengers to mind the gap, large vertical and horizontal gaps between the train and the platform are even more common on the main line railway.

This presents a risk for passengers on an otherwise very safe mode of transport. Platform Train Interface (PTI) incidents lead to around 13 fatalities each year in the UK, and comprise 48% of the passenger fatality risk on the mainline railway network, according to the Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB).

For wheelchair users, and many other passengers with mobility impairments, a step of a few inches may as well be a ten-foot wall. With few exceptions, station or train staff need to deploy a manual ramp to provide level boarding. This assistance typically needs to be booked 24 hours in advance. As many wheelchair users will attest, booking this assistance is no guarantee that it will actually be provided. Sadly, mobility impaired passengers cannot simply ‘turn up and go’ on Britain’s mainline railway network.

Train operating company focus groups, even those about passenger information, regularly receive feedback on the need for step-free access. Parents with buggies, people with strollers, seniors with limited mobility, passengers with luggage, cyclists, and shoppers with large purchases all benefit from accessibility improvements. For people to become car-free, they need alternative mobility modes that are flexible and accessible. Accessibility is no longer seen as a nice-to-have, but rather the legal and ethical obligation of a public service.

Street To Platform

Discussions about the platform train interface are moot if the stations themselves are not accessible. Whilst many passengers with reduced mobility can overcome a single step, a flight of stairs is another matter entirely. Approximately one in ten National Rail stations lacks step-free access from street to platform, with at least some platforms accessible only via stairs, subways, and footbridges.

Unfortunately, retrofitting a lift (usually two, one for each platform) is a costly business. The recent £6m step-free upgrade of Southeastern’s Bexleyheath station in South-East London included widening the London-bound platform to accommodate the new lift and footbridge. The lift will be able to carry up to 16 people and handle large wheelchairs, in compliance with current standards. The project was funded by the DfT’s Access for All programme.

Other recent station retrofit estimates, however, have come in at £15-20m for a pair of lifts and the associated footbridge, with costs depending on site conditions and the scale of work involved.

Even then, these works stop short of true step-free access whilst the platform-train interface problem remains largely unresolved.

Platform to Train

Ideally, the platform matches the floor height and width of the trains, with only a few millimetres of gap. This is exactly how it’s done on modern metro and tram systems worldwide, which operate a more-or-less uniform fleet of trains.

On the self-contained sections which comprise the majority of the Tyne and Wear Metro and Merseyside’s Northern and Wirral Lines, this strategy has made level boarding the norm.

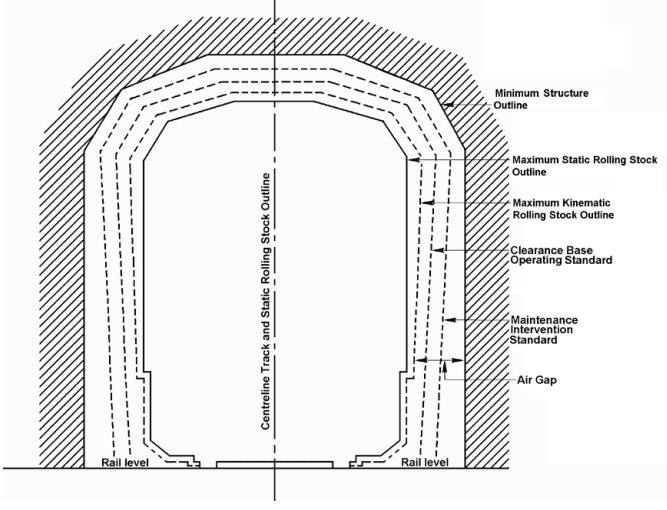

On the main line railway, things get more complicated. Platforms must be set further back from the rail to accommodate the kinematic envelope of various types of trains cleared to pass through the station, potentially at speed. The width and lateral movement of freight trains is a particular constraint, especially on routes cleared for container traffic.

The difference is evident at Canonbury station in North London: The Mildmay Line (née North London) carries freight, hence the platforms are too low for level boarding onto the class 378 units. The Windrush Line tracks through the station (the East London Line extension) do not carry freight, so their platforms are flush with the floors of the same EMUs.

Great Britain has a nominal platform height standard of 915mm above the railhead, offset 730mm from the closest rail. This is, as they say, honoured more in the breach than in the observance. There are significant variances, and it has been known for freight trains to scrape platforms.

The typical approach in passenger train design for getting close to platforms, but not too close to scrape them at speed, has been a higher floor: Typically around 1,100mm above the railhead. This creates an approximately 200mm step up to board, but in so doing allows a fixed step to bridge the horizontal gap without fouling the platform.

Ramping Up

Accessibility from platform to train is regulated by the Technical Specification for Interoperability for Persons of Reduced Mobility (TSIPRM), largely dating from the 1990s. Crucially, these documents do not require level boarding, only mandating the maximum step and gap dimensions beyond which a ‘boarding aid’ is required.

Hence the overwhelming majority of UK trains complied with the platform-train and on-board requirements by the 2019 mandate. Boarding by means of a manual ramp remains the norm, leaving wheelchair users dependent on staff assistance.

As for the majority of those with ambulatory disabilities who don’t use a wheelchair, including many older people, the steep angle and lack of grab rails can make a ramp more difficult than a step.

There was a somewhat infamous accessibility case of CrossCountry staff insisting an elderly lady with a walking stick use a ramp because assistance had been booked, even though she found this more difficult. All she wanted was a hand with her suitcase, as she only had one free hand. Here, good accessible design would have included grab rails and a more flexible approach to assistance.

The portable ramps provided on the new Welsh class 197 trains have introduced new lows in terms of usability, as described in detail in the February 2023 edition of Modern Railways. Many stations have a collection of portable ramps, one each for a different type of train, as there is no standardised method for securing them to trains. In some instances, some fleets need longer ramps than others to ensure they don’t exceed a slope of 1 in 20. There has been a recent Innovate UK/South Western Railway competition launched for the design of a better ramp.

The Disabled Persons Transport Advisory Committee (DPTAC)’s independent report DPTAC reference frame: Working towards a fully accessible railway gives the context:

Disability affects around 14 million people in the UK. It includes physical and sensory impairments as well as non-visible disabilities, such as autism, dementia and anxiety.

For many disabled people their inability to use the rail network, because of physical or other barriers, or because of a lack of confidence, prevents them from being able to access employment, education and health care, as well as participating in leisure, social and commercial activities.

Although there has been worthwhile progress in improving the accessibility of the rail network in recent years (improvements to the accessibility of rolling stock for instance), evidence continues to suggest consistently that the network nevertheless remains substantially inaccessible for many disabled people…

Against this background, we have argued over the past 2 years that accessibility needs to be seen as a fundamental requirement of a successful railway, embedded into the core of what the railway does in the same way that safety already is.

The report gives the following state of accessibility of the main-line railway network:

Only 20% of national rail stations have step-free access between street and platforms. A further 31% of stations have ‘reasonable’ step-free access, usable by many, but not all, disabled people.

Less than 2% of stations have level access between train and platform – meaning for the other 98% a platform-train ramp is required, along with manual deployment by staff. At 33% of stations, there is a vertical or horizontal step or gap greater than 25cm.

Filling The Gap

The railway industry has adopted two approaches to step-free access without the need for a ramp. The first is to raise platforms to match traditional floor heights on the self-contained segments of particular lines.

For example, Crossrail built the central section of the Elizabeth Line to a platform height of 1,100mm, matching the floor height of the class 345 trains. This has the deleterious effect of making level boarding impossible outside of the central section, where some freight and other passenger trains remain. Heathrow Express provides level boarding at 1,100mm throughout, as all of its platforms are either dedicated or shared with the Elizabeth Line.

The second is to procure lower-floor trains. Swiss manufacturer Stadler has taken this approach when supplying DMUs and EMUs from its FLIRT platform to Greater Anglia and Transport for Wales (TfW), and Class 398 tram-trains for TfW’s Valley Lines with a 960mm floor height. This approach results in a wider horizontal gap, requiring retractable gap-fillers which can either be carried on trains, or with intelligent platforms.

The lower-floor train plus gap filler approach is favoured by the Campaign for Level Boarding because it can be implemented network-wide given incremental platform rectification to the established 915mm standard above the railhead.

The extra moving part does introduce an extra failure mode, increasing the potential for operational failures in service and associated disruption. This is particularly true for smart platforms, failures on which could potentially make the line impassable. Further, small changes in height between train, gap filler and platform can also create trip hazards that potentially affect a far greater number of passengers. particularly blind or partially sighted individuals. Current building design and rail practice generally specifies minimum step heights; widespread implementation of gap fillers may require alternative mitigations.

Unfortunately, there is no national program to resolve the various National Rail platform heights, as we have discussed. Without that, widespread national standardisation of train floor heights cannot happen.

Does an Extra Crew Member help?

In recent years, British transport policy has been moving towards leaner staffing on the railway. Whilst a national policy to close most ticket offices was abandoned, on a local level an increasing number of stations lack a ticket office or any staff at all for much of the day. This has been a concern for disabled passengers, who need to be able to find a member of staff in order to travel spontaneously, or if booked assistance fails to show up.

On board, meanwhile, new trains increasingly feature driver-controlled operation, wherein the driver, rather than the conductor, is responsible for opening and closing doors. Whilst this has raised fears about conductors being eliminated altogether on more routes, conductors will be able to devote more attention to their customer-facing roles such as assisting disabled passengers. Currently the biggest source of missed accessibility assistance requests is staff failing to read the message (eg ‘deploy ramp at Flimby’) in time, which driver-controlled operation may mitigate.

It is noticeable that the trade union messaging on Driver Only Operation has subtly shifted from ‘who closes the doors’ (although this remains a live issue) to ‘who helps people with mobility issues at unstaffed stations, and looks after passenger questions and issues’.

Some train operating companies arrange for staff to travel by road to meet trains where assistance has been pre-booked. This solution has obvious challenges, for example traffic delays, and peaks and troughs in demand for assistance.

HS2 Accessibility

HS2 train accessibility will be challenging on a technical level. It is believed that they have decided to have 1100 mm platform heights at all new stations, as well as a much larger than usual offset to accommodate the ‘captive sets’ originally planned to match wider European high speed rolling stock and operate exclusively on HS2 trackage. The trains being ordered for now will be to the normal UK loading gauge, so there will be a significant gap to fill at HS2 stations, whilst the usual ramps will be needed once the trains come off the HS2 network and onto the classic rails.

On new platforms, there will be level gap fillers on classic compatible stock along with angled gap fillers for existing platforms, most of which are on container freight routes. A number of companies are bidding to build HS2 trains, of which every European rolling stock manufacturer apart from Stadler and those from the former Warsaw Pact countries now has a conventional floor height (~1150mm) to 915mm gap filling solution.

Accessible Transport Legal Obligations Inquiry Begins

The parliamentary Transport Select Committee launched a Call for Evidence public survey for its Legal Obligations Inquiry, to hear about the barriers that people with disabilities and accessibility needs experience when using public transport. This included buses, trains, taxis, planes, as well as using streets. The survey closed 20 March 2023.

There are a number of legal obligations to ensure accessibility applies to transport operators and local licensing authorities across different modes of transport, and the Committee wanted evidence about the following:

How effective is the current legislation aimed at ensuring accessible transport for all?

How can the current legislation be better enforced to make accessible transport a reality?

How effective are the relevant regulators at enforcing accessibility in transport?

Do the current legal obligations or guidance need to be strengthened?

How effective is the Government’s Inclusive Transport Strategy?

How well does Inclusive Transport Strategy influence decision-making across transport policy?

How could the Inclusive Transport Strategy be improved?

We look forward to reading the recommendations of this Committee’s report once it is issued.

The Accessibility Requirement of Rail Replacement Buses

Not mentioned so far is the challenge of carrying everyone when rail replacement buses need to operate. Traditionally, all sorts of vehicles were employed, typically including touring coaches operated by Britain’s many small coach firms, which were not required to have wheelchair access. People with mobility impairments were conveyed in taxis.

Following a 2019 legal challenge it was held that rail replacement buses were ‘scheduled services’ and therefore needed to have wheelchair accessible vehicles. This precluded the use of touring coaches, which companies couldn’t replace overnight. In any case, this issue is likely dwarfed by the general shortage of bus and coach drivers. In recent years some leading to some rail replacement services not being provided at all. At times, passengers have been told to book their own taxis and claim from the railway.

There many other Platform Safety Issues

There was a fatality at Eden Park Station in 2021 at which a person with impaired vision fell onto the track. He had not noticed that he was near the platform edge, as there was no tactile surface indication there, so he fell and a train fatally struck him.

A recent incident has motivated the individual who fortunately survived a similar fall to sue Network Rail for the same lack of platform edge tactile edges. We await the outcome with interest.

Great Western Railway (GWR)’s Twyford station in Berkshire has had a number of incidents due to its platform sloping towards the tracks. In May 2022, a baby in a pram rolled onto the tracks. Fortunately, the baby was rescued unharmed after the mother and a fellow passenger lifted the pram to safety. However, the incident sparked a review of the station’s layout. New Civil Engineer magazine read the minutes from Network Rail’s board meeting about the incident and found that a similar incident occurred a month later, when an empty pram fell onto the tracks due to the turbulence caused by a passing freight train.

GWR’s investigation found that the platform was originally constructed in 1839 with a shallow, one-degree gradient towards the track to assist with drainage. Fortunately, the designs of new UK rail platforms no longer use this design, as the platform gradient now directs water run-off away from the tracks.

The Rail Accident Investigation Branch (RAIB) investigation concluded that the cause of the second pram accident was a freight train’s slipstream, combined with the ambient wind, which generated an aerodynamic force which overcame the brakes on the wheelchair. As a result, the RAIB made five recommendations:

Inform the public of the potential hazards from train slipstreams and the need to apply brakes and keep a hold of wheelchairs and pushchairs when non-stopping trains pass through stations;

Investigate measures to improve the safety of wheelchair and pushchair users at railway stations;

Change the Railway Group Standard which specifies when a station operator must carry out a formal assessment of the risks from passing trains.

Make two recommendations to Great Western Railway: to continue its current work to risk-assess the platforms for which it is responsible, and

Ensure that warnings of passing trains provided to station users are timely and effective.

This sounds quite passive, and in all likelihood similar accidents will continue to occur—more signage does not make an area safe.

To go Up, or to go Down

There are two ways to bring platforms up to the standard height—either raise the platform or lower the track. Permanent way engineers really don’t like lowering the track as it leads to water accumulating, which can be notoriously difficult to resolve. Of course, it is sometimes necessary, such as to obtain extra clearance under a bridge.

Raising platforms can cause a problem too. East Croydon platforms 1 and 2 were quite low compared to the trains’ floor level, which had led to a number of problems. Network Rail did an excellent job of installing a lightweight top surface, which can be a good solution. However, it was expensive because nearly all the work had to be done at night to avoid closing the busy platforms, and the recently installed lifts needed a ramp up to the new platform level. This is unfortunate, as a slope entering or exiting a lift can create extra mobility challenges.

Clapham Junction is a notorious network pinch point, and one regular LR commenter has argued that dwell time could be substantially reduced if the currently substandard platforms were higher. This is probably a very good idea, but as at Croydon, this would add a slope down to the lifts. As for the steps down to the platforms, uneven step heights represent a safety hazard, so either the platforms would need to be raised by the full height of a step, or else a slope would be required to and from the stairs too.

In places, the problem is simply not bothering. For example, Maidenhead Crossrail station has a large drop from train to platform 3. This station had been modified with expensive lifts, yet at least one of the platforms used by Crossrail is not standard height.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Under current policies, station closures are triggered by major infrastructure costs that undermine the benefits. This can be an issue for lightly used stations, which comprise the majority of stations on the network, the costs of implementing accessibility are such that the station would close, with all passengers losing out.

Pragmatism is an art, and here this may take the form of finding economical ways to provide accessible service at minor stations.

For more detailed, engineering based, look at the UK mainline rail network’s status and improvements of level boarding, watch Gareth Dennis’ Rail Natter Level Boarding video.

It’s Generally Worse on The Continent

So how are other European countries dealing with this issue? Train accessibility is actually one area where the UK is doing better than Europe, on the whole.

Despite the UK’s 24-hour delay from requesting to receiving accessibility assistance at main-line rail stations, continental Europe can be even worse, having an unholy myriad of platform heights. Passengers there sometimes need to climb up 3 steps or step down to the lower level of a train. As a result, ramps would have such a steep slope that they are impractical to use.

It is acceptable on the Continent to procure high floor trains, with one or two doorways at level access to typical platform height. It appears that this approach (the opposite of platform humps) is offered by all the main train manufacturers and could be adopted for UK operation. But no whiff of this to date.

Germany, that (supposed) Paragon of Efficiency

As an example of difficulties on the continent, let us look at Germany, which is a well regarded marvel of engineering. Correspondent NCT took a tour of Germany’s many tram and railway lines a few months back, armed with an Interrail pass and a 9-Euro ticket, as follows:

The Rhine-Ruhr is a polycentric region with a lot of challenges – it suffered from heavy Allied bombing and everywhere has a slight Coventry look about it. The Rhine cities have traditionally been the country’s struggling cousins. The public transport networks of Dusseldorf, Cologne, and the Ruhr valley cities (Duisburg, Essen, Dortmund) are certainly extensive, and they offer valuable lessons for British regional cities, in both how to and how not to plan and build effective public transport.

All of the Rhine-Ruhr cities have Stadtbahn systems, sometimes supplemented by conventional trams. The former are usually high-floor trams that often dive underground in the city centres, whilst the conventional tram systems are usually, but not always, low floor.

However, these cities are still struggling to work out what to do about floor heights. Cologne (Köln) is probably the closest in terms of separating its high and low-floor systems. Its efforts have been frustrated by the second north-south tunnel’s collapse – but work is continuing slowly, with an estimated opening date of 2029.

German Urban Rail Networks’ Accessibility

Dusseldorf mixes its high-floor and low-floor services in the suburbs, and it is not clear how they will make routes accessibility standard compliant without fundamentally changing the route structure. In Essen, the distinction between trams and Stadtbahn is even more fuzzy – one tram route shares the tunnelled route with the Stadtbahn and currently uses high-floor vehicles. The local authorities have flip-flopped whether to make it all high-floor or low-floor, and now going either way involves some substantial compromises or work.

A couple of Munich tram lines also have some stops in the centre of the road, requiring crossing the active carriageway to board and alight. No chance of level boarding there.

The infrastructure maintenance cost delta from going from tram stops to metro stations is major and should not be under-estimated. It is evident that even Germany struggles to find the money to maintain and properly upgrade its infrastructure.

Like the UK, most of Germany’s rail systems evolved before modern accessibility and health & safety standards, so they had built considerable infrastructure that would not be permitted to construct today. Generally, Germany adopts a pragmatic approach – if an improvement will cost a lot for small gains, they don’t proceed. Funding is tight there too.

Level Boarding in every Country is a Continual Work in Progress

Unfortunately, in the all too frequent times of austerity, UK platform-train interface upgrades are demoted in priority in the Treasury’s funding process. This is despite such upgrades benefiting all users, in the form of reduced accidents, quicker boarding and alighting (hence reduced dwell times), and station flow improvements.

There is no magic solution – often just plenty of compromises based on each line and station’s situation and context.

Thanks to the LR Towers Brain Trust for the detailed information for this post. Also thanks to NCT for his 2022 Euro Trip report on German platform-train interfaces. Lead photo is Vauxhall station. Network Rail

The post Much ado, or not to do, about Level Boarding on Network Rails: Part 2 appeared first on London Reconnections.