The Covid pandemic has had a lasting impact on Britain’s railways. Undoubtedly the most significant impact has been on changing travel patterns in general and, in particular, a reduction in commuting and other business travel which is not expected to ever fully return. Possibly the second most significant long-term impact is an acceleration in changes to ticketing. This was something that was already happening but Covid has focused minds and speeded up a revolution that was already gathering pace. We look at significant changes that are happening and may happen in the future.

Abolition of much of First Class Travel

First Class travel does not affect many people – and that is really the whole point. With the standard of comfort in Standard Class rising over the years, there is less that differentiates between the two classes of travel. Nowadays, First Class accommodation is sometimes officially declassified and often effectively declassified by others either deliberately flouting the rules or simply overlooking that the accommodation was only for passengers with First Class tickets. Its days on many routes may be numbered judging by the recent decline in services that still offer First Class travel.

Possibly one reason for retention in British Rail days was that First Class travel was a highly prized perk by all levels of management – the very people who would be responsible for its continuation or otherwise. This perk is now only available to relatively few people and is probably not treated with the protective instinct that it once was.

Since privatisation, Chiltern Railways probably started the ball rolling with only Standard Class from the outset, although for a while they did introduce a business zone on their few loco hauled trains. Likewise, c2c have never had First Class, and about five years ago Anglia culled it from all but their Norwich inter-city services.

The trend is clearly to remove First Class from commuter railways and save it for long distance quality travel. It is not the money-spinner it once was imagined to be, and today’s continuation may be more about not losing business altogether from passengers who would probably travel either First Class by rail or by other means of transport for their longer journeys.

It has to be borne in mind that a 25% reduction in seats by a typical First Class seat arrangement (1 + 2 seating) requires a 33% increase in revenue to raise the same fare income from Standard Class (2 + 2 seating), and that assumes that seat occupancy rate (as a percentage) is unaltered. With that generally not being the case, it is clear that providing First Class travel is both a money-loser and an ineffective way of using one’s assets.

Nowadays, in commuter stock, the seating arrangement is often the same for First Class as it is Standard Class, with possibly a little more legroom. It therefore can seem to the passenger that the fare is a third extra than Standard Class with no discounts available for the privilege of having an antimassacar on one’s headrest.

What probably brought the First Class issue to a head recently was SouthEastern’s discovery and revelation that post-Covid they only had 29 First Class season ticket holders. The decision to end First Class travel on their services was a no-brainer. This may have helped LNWR come to a late decision to abolish First Class from the May 2023 timetable. The new Class 730 trains for LNWR that aren’t already complete will be configured for Standard Class only, and ones that currently have First Class accommodation will be retrofitted to be Standard Class only before entry into service.

Expect South Western Railway and Govia Thameslink Railway to follow the trend towards abolishing First Class with keen interest. Govia would probably like to remove First Class from Thameslink trains, which can become quite full and have an awkward arrangement where some First Class seating is declassified south of Farringdon. This could be achieved at almost zero cost by simply declassifying the currently designated seats, or an arrangement with Siemens could be made to reconfigure the relevant carriages which might workout surprisingly expensive for what would appear to be a simple modification.

As stated at the start, First Class accommodation is probably not a significant change to many people but, in terms of being willing to make drastic changes to the ticketing regime on the railways, it does indicate that nothing is sacred. If First Class travel is becoming a thing of the past, what other significant ticketing policies will change?

The Demise of Season Tickets

A feature of Covid, quickly felt, was the refund of almost all season tickets as they were no longer required. As the government was asking us (or telling us) not to travel except for essential reasons, they obviously felt obliged to refund unexpired season tickets without penalty. Only essential workers really had a reason to keep their season tickets.

Once the dependence on season tickets was broken it was going to be hard for commuters to return to the habit of using them. Unless they regularly went into the office for five days a week, it often made more sense to simply pay-as-you-go with an Oyster or a bank card. This would also increase flexibility at a time when one did not know if a new wave of Covid would come along and require full-time working from home to recommence.

A secondary effect of the demise of season tickets was that every day one went into the office cost real money in daily travelling costs. So, in some cases, this could swing a decision as to whether to go into work or not. In other cases, it was realised that minor modifications to working times could mean that an off-peak fare could be charged. Along with this was the consequential further reduction in income to the railway operating company – which is usually effectively bankrolled by the DfT these days. With Wi-Fi on trains, some people realised that they could adjust their working hours at the office and perform basic office tasks such as checking emails on their commute in order to qualify for off-peak fares.

Why have Season Tickets?

The demise of season tickets reignites the issue of why have season tickets at all? They really don’t make much sense in an era of wave-and-pay.

The traditional advantage for the railways of getting money ‘up front’ no longer holds. They can nowadays borrow money much cheaper than the discounted rate for a season ticket. With few people nowadays actually walking up to a ticket office counter to buy a ticket, the removal of the burden of the ticket office having to sell a ticket on a daily basis to regular travellers no longer applies.

It will be interesting to see if there are any future moves to eliminate season tickets. One obvious stealth approach is to withdraw monthly season tickets and include a monthly cap on wave and pay, although this would probably be quite complex to introduce.

If season tickets were to continue it seems that the basis for charging them needs to be reconsidered. The number of days a week at a daily rate required to justify a season tickets is tapered depending on distance, but 3.6 is a typical figure for a commute entirely within the London fares zones. This really doesn’t make it worthwhile for a person commuting for four days a week, given there will be days off for holiday, sickness, and possible work activities that may require a different journey (and therefore the fare is claimable on expenses). One expects that the revenue analysts will be crunching a lot of entry and exit numbers trying to work out an optimal level to charge so as not to lose too much revenue, whilst also encouraging people to make a commuting journey for more days per week.

The Rise of Split Ticketing

Split ticketing is the process of purchasing two tickets to cover a journey when this works out cheaper than buying a single through ticket. It has been around for decades but was little publicised. Its roots generally lie in scenarios where it was felt that a fast inter-city service would justify a premium over the slower and less-comfortable ‘slow’ service over the same line.

Split ticketing was often regarded in a similar manner to a legal tax dodge. Take advantage of it if you are in the know but keep quiet about it. The reason for keeping quiet was partly because it was seen as a legal way of cheating and therefore nothing to boast about. There was also the issue that, if it became too well known, measures would be taken to eliminate its use. In fact, a few years ago a restriction was put into place in the National Rail Conditions of Carriage requiring the train to actually stop at station where the split occurs but, other than that, it seems it would be hard to impose restrictions on its use.

With the rise of websites encouraging you to book your train tickets through them, split ticketing is openly seen as a selling point which enables cheaper fares to be offered. As well as the more straightforward split ticketing, the generally increased flexibility with travel arrangements and the savings that could be made has encouraged time-dependent split ticketing where avoiding peak hour fares can make a massive difference. For example, an expensive peak journey from East Croydon to Cardiff could be significantly cheaper if the Cardiff train departs from Paddington after 0930. Simply buy a ticket (or use contactless) from East Croydon to Paddington to cover the peak travel element and buy a separate ticket from Paddington to Cardiff.

This rise in split ticketing has reached the extent that businesses and other organisations (including government-supported charities) openly ask employees or volunteers to investigate whether their fare could be reduced by using split ticketing. We are led to believe split-ticketing now has a considerable impact on revenue and the DfT is concerned about the future consequences of this.

Closure of Ticket Offices

It seems to be a widely held belief that the government (or at least the Department for Transport) has a strong desire to close ticket offices at all stations, other than those where they can be commercially justified. Ticket office usage is now extremely low, yet there is a considerable lag in closing offices.

It cannot make sense for stations like lightly-used Tattenham Corner to be open from early morning until late evening or for Coulsdon Town to be open for similar hours. In the latter case not only is it one of the ten least used National Rail stations in the Greater London area, but Coulsdon South station is fairly close nearby as an alternative and, despite Coulsdon South being much busier, the ticket office isn’t open for such long hours.

There seems to be little doubt that Covid has brought about a reduction in practice in the number of ticket offices open and the hours that they are open for. It is salient to note that there is little or no clamour to ensure that opening times pre-Covid are restored.

Ticket office closures are particularly stark on SouthEastern where, post-Covid, many stations appear to be totally unstaffed for most of the time. It is generally hard to find a ticket office that is open and even such major stations as Lewisham, Greenwich, or Woolwich Arsenal seem to lack ticket office (or even any other) staff at the station.

In the case of SouthEastern one feels these closures have gone too far with nothing done to provide alternative facilities for those inconvenienced. In other words, the problem seems to be made much worse by the fact that this appears to have been done in a haphazard disorganised manner rather than according to any plan that has been put into place. Given that most train operating companies are, to a less or greater extent, in a similar position it seems that such a plan needs to be conceived and implemented at a higher level.

The Add-on Ticketing problem

The haphazard closing of ticket offices highlights issues where passengers have a legitimate need to purchase a ticket other than from the originating station. Most ticket machines only sell tickets from the station they are located at. One can understand the reluctance of most train operating companies to provide facilities of purchasing tickets from any station to any other station. It could lead to massive fare evasion with, for example, someone walking to an unstaffed South London station and purchasing a local ticket from Preston Park (just north of Brighton) to Brighton in order to make an illegal low-cost journey and exiting through the ticket gates at Brighton.

Some railway companies encourage passengers to purchase tickets on their phone. This, obviously, is available between most stations and this may have the same risk of fraudulent travel as a from-anywhere-to-anywhere ticket machine. One can expect this method of travel purchase to be encouraged in future as more barriers become compatible with optical scanners being added to active ticket gates when presented with a valid QR code displayed on a phone.

Caught in the crosswires, as it were, with add-on ticket issues are passengers with a legitimate need to purchase tickets not available from ticket machines. These passengers may also not be comfortable buying tickets with the phones – or simply may not be able to do so. Two categories of passengers stand out.

Season tickets and other zonal tickets can create a problem for when passengers wish to travel beyond the zones their ticket or Oystercard is valid in. These customers need an add-on card. Unlike split ticketing, in this situation there is no actual requirement for the train to stop at the boundary station. If they have a season ticket and the destination station has card readers then there isn’t an issue – they simply tap out. Otherwise, the only really practical way to purchase these tickets are at a ticket office or on a smart phone.

Passengers with 60+ concessionary cards or London Freedom Passes can quite often have a legitimate need for an add-on ticket. For some journeys, especially return ones, there can be valid reasons for requiring a ticket from the zone 6 border rather than a specific nominated station. These situations, in general, are just not adequately catered for.

And, dare one say it, in a similar vein it could be argued that the person wanting to make a split ticket journey, which is perfectly legal, also needs a ticket office to be open to purchase their tickets or, alternatively, an ability to use a smart phone.

Project Oval

At this point you might be thinking that what is needed is a comprehensive rethink of the way rail deals with ticketing. You might think that TfL has gone a long way to put something suitable in place but more needs to be done. And it needs to be implemented beyond London as well as within London. Welcome to Project Oval.

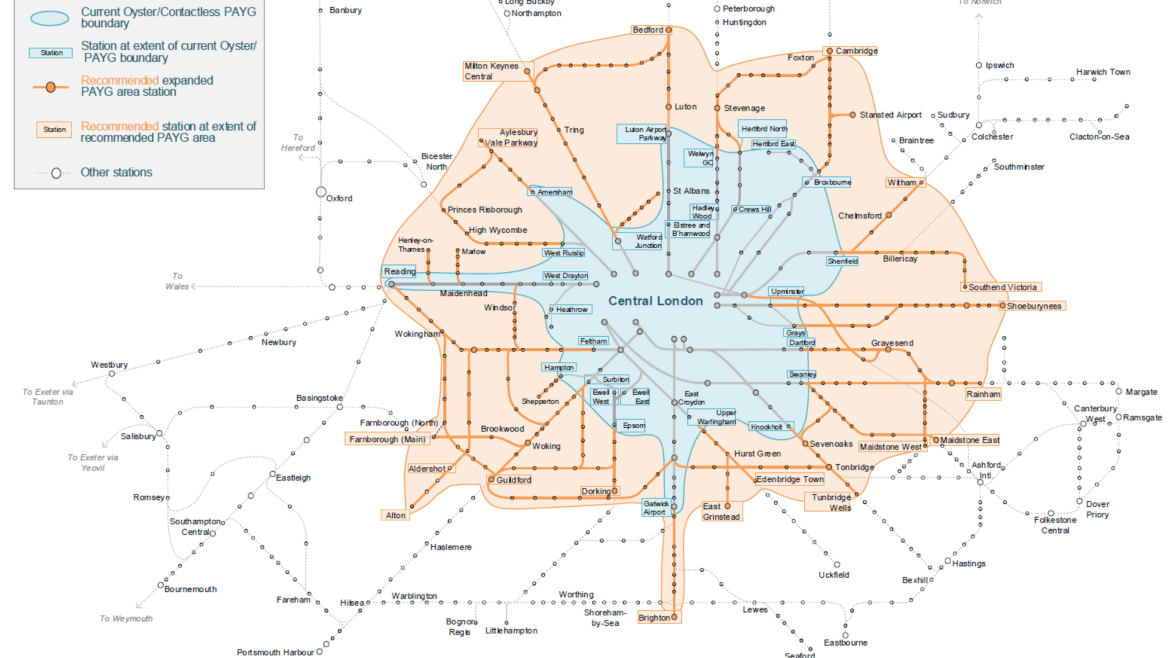

Project Oval is a DfT sponsored plan to encompass all travel using pay-as-you-go technology in the South-East of England. The initial plan is to cover more than 230 stations, but bear in mind that includes stations already covered by pay-as-you-go. Exact details are sketchy as to where will be initially covered but the first phase seems to be quite a significant expansion of the area covered by the London zones. Initially not all features will be implemented with, for instance, discounted travel still requiring paper tickets for the foreseeable future.

What does seem fairly clear is the area ultimately intended to be covered by the current scheme as indicated on the map above. In fact the map is slightly out of date as, in advance of this, the Henley-on-Thames and and Marlow GWR branches already have contactless travel hardware installed and in use.

GWR POSTER SHOWING EXPANDED CONTACTLESS AREA

At present, the scheme is intended to be an expansion of TfL’s pay-as-you-go technology, administered by TfL on behalf of the DfT. Ultimately, it seems that the DfT is keen to tender the work out and remove TfL’s responsibility for administrating the scheme. Such an approach makes sense as the DfT don’t really want to be reliant on TfL. One also suspects that certain government ministers who do not like TfL and the current London Mayor for various reasons would not like TfL to have any leverage over the government.

TfL, for their part, would probably be happy, in principle, for this work to be taken off them so they can concentrate on providing a good passenger service rather than administering collecting the revenue. In practice and in the current economic climate they probably welcome the extra revenue (as a slice of the fare paid) enough to want to hold on to any future contract, so long as it is financially worthwhile to do so.

Friday is the New Hybrid Day

Finally, post-Covid society has brought into sharp focus the way Friday is becoming less and less a staple part of the working week. For the most part, the railways have so far failed to respond although Avanti seem to be already treating Friday as an off-peak day.

An obvious benefit, to society as well as the railways, of making Friday an off-peak day is to encourage people to work in the office on a Friday instead of one of the busy mid-week days. Railway companies have not yet got to the point where they have a Monday-Thursday timetable and a Friday timetable, but some services are now made up of fewer carriages on Mondays and Fridays. Some London bus routes (e.g. route 133) already have a different timetable for Friday.

Off-Peak all day Friday fares have already been suggested as something TfL could introduce. This was immediately rejected by TfL and the Mayor due to the loss of revenue that would entail. Whilst that is a valid argument not to remove peak fares on Fridays now, it is not necessarily a good argument at the next fare revision. Simply put, ‘Off Peak Friday’ could be introduced in a revenue neutral way if other fares were adjusted to take this into account.

Further pressure could be brought to bear for the Mayor to reconsider the pre-9.00 a.m. ban on free travel for those with 60+ and Freedom Passes on Friday. Loss of revenue is cited for the now-permanent removal of the free journeys before 9.00 a.m., but one does wonder what the actual loss of revenue would be if this facility was reinstated on Fridays. Unlike peak journeys in the morning on Mondays-Thursdays, the cost of providing the facility would be truly marginal with the small potential loss of revenue being the only significant factor.

How Will the Future see these changes?

One cannot predict how future railway historians will look at the current period of the railways in Britain when writing their history. For one thing, we don’t know how these changes will pan out. But one thing that is clear is the railways are currently in a period of rapid change. Unlike many other periods of change (e.g. nationalisation, privatisation) this was not a planned change but one forced upon it by a changing society.

Whatever happens, we are pretty sure that purchasing your rail travel in five or maybe ten years from now is going to be very different from how it was done in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Thanks, as usual, to ngh for supplying a lot of the background information

The post Rail Ticketing in a post-Covid World appeared first on London Reconnections.