“I wanna be the leader, I wanna be the leader.

Can I be the leader? Can I? I can?

Promise? Promise?

Yippee I’m the leader, I’m the leader.

OK what shall we do?”

Roger McGough

Any Colour You Like

Come 5th July 2024, there is a new Labour government, voted in on a strongly-supported mandate, and pledged in Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s lunchtime speech to ‘get on now’.

We’ll focus in this short review on how Labour is starting at a fast pace across many fronts despite the financial and legislative obstacles, and what this can mean for planning and transport developments. It sets the context for what will be key factors during the next five years, maybe longer, which influence priorities and delivery outcomes.

As reported in most media, Labour fought its campaign on a manifesto centred around boosting the UK’s sluggish rate of economic growth in recent years. The housing shortage was also a major issue. The party pledged to achieve results largely through changes to the planning system, and by making the country more attractive to inward investment.

However, moving the economy forward faces a challenge with weak public finances. The party also plans to overhaul UK employment law, reshape the railways, set up a state-owned energy investment and generation company, and boost green investment.

Party Sequence

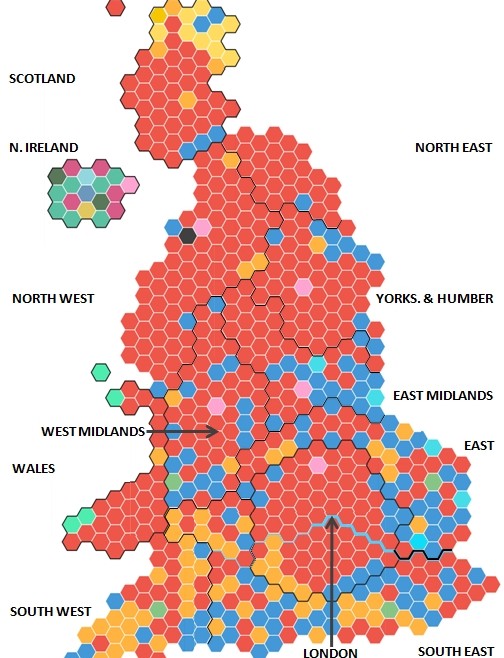

The direct election results are available from BBC News. There is mapping in geographic and histogram form, and further data links to each constituency. With five exceptions, each of the UK’s 650 seats have roundly 70,000 electorate +/- 5%.

Although many shire areas in England returned a Conservative MP, the bulk of Britain’s major urbanised (and some rural) constituencies elected a Labour MP, because of Britain’s ‘first past the post’ system. This is highlighted in the histogram which shows equivalent population-sized areas.

In turn this emphasises the significance of the urban form in Britain’s voting demography, and provides the context for many of the new Government’s initiatives. Urbanisation of parts of the East of England and a return to historic voter preferences elsewhere helps to explain Labour’s recovery – there isn’t much left of Boris’s ‘blue wall’. LibDems also recovered many rural and suburban areas with the fall-away of Conservative support.

Dark Side of the Moon

Reasons for the electoral reversal are simple and are mostly a negative statement about the previous Conservative Government, with loss of voting volume to other parties:

Smaller core popular vote because of previous leadership changes, the Liz Truss budget miscalculations which added to inflation and household costs, and the high energy bills arising from the Ukraine war.

Party in-fighting and stagnation of new ideas, mirrored by re-invention of UKIP as the Reform party which was attractive to voters with conservative views.

Consequences of capital and revenue spending constraints imposed by HM Treasury in the absence of significant economic growth, compounded by the trading effects of Brexit and continuing productivity shortfall after Covid in back-to-work numbers.

Collapse of the SNP core vote after that party’s internal problems.

Labour policies for rapid change and action on the economy, planning, and housing, paralleled by LibDem policies centering on a ‘fair deal’ for voters.

The expansion of electoral interest in other parties and issues had knock-on effects in other ways – examples being some loss of Labour support by Muslim voters, because of its handling of the Gaza issue, and successful constituency targeting by LibDems and Greens. Former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn retained his Islington North seat as an independent.

The overall outcome has been (2024 vs 2019 based on the new seat distribution): Labour 412 vs 201 (incl. Speaker 1), with 326 seats needed for a majority, Conservative 121 vs 372, LibDem 72 vs 8, SNP 9 vs 48, Reform 5 vs 0, Plaid Cymru 4 vs 2, Greens 4 vs 1, and Independents 5. Northern Ireland has 18 seats, however Sinn Fein does not take its 7 seats.

How does this translate into strategic actions by the new Government?

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

The British convention is that nowadays a possible incoming party is extensively briefed by civil servants about the work and funding of individual Departments during the months preceding a General Election, whilst the shadow Government shares its thinking and priorities in return. This helps a smooth changeover on the due day.

Beyond that, there are six main factors to be addressed by a new Government:

‘Must-do’ top-line manifesto priorities.

The state of national finances and international bond-raising, allied to economic aims.

Expenditures authorised by previous Governments, and the scope to vary those.

Westminster’s relationship with the different UK nations and regions, and wider relationships with local government, public industries and other delivery partners.

How Government Departments are to be structured to support programme priorities.

Operational consequences of the election timing, on parliamentary working weeks, holidays, party conferences, King’s Speech, legislative activity, budget scrutiny and timing, annual and quinquennial regulatory programmes, etc.

The Wall

The immediate reality is that Labour doesn’t know the full extent of the national financial shortfall, but that there is a big one. It is known that the Conservative Government had run out of spending headroom because of slow economic growth.

Departments had significant sign-offs deferred to avoid ‘booked spending’, whilst there is a second waiting list of ‘pencilled-in for the future but not signed off’. So scrutiny of budgeted spending wasn’t invoked and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) rules were adhered to nominally, but the government financial carpet was looking blue and lumpy.

Rachel Reeves, the new Chancellor, has already warned of the “worst economic inheritance since the Second World War”, commenting “there is not a huge amount of money there”.

Labour will have to choose between running a Conservative budget for 1-2 years, or incur some months going through the books to define the deficits and prepare a Comprehensive Spending Review, and/or invoke private sector participation in projects requiring new funding. She is already leaning towards the latter. The timing of a CSR may follow soon. The normative month for an autumn budget and public spending permissions for the following financial year has been November, though tighter margins for announcements have occurred recently.

Simultaneously the timing of the election has meant there could be a long wait for primary legislation, with the summer parliamentary recess and party conference weeks due between now and early October. Large new Acts of Parliament will take months to process through their stages in both Houses, although Labour can be sure of getting them through because of their large majority.

Welcome to the Machine

Sir Keir Starmer, the Labour leader and now Prime Minister, was convinced that his party must begin its first term of office running, and not delay action during early months. This was underlined by the scale of the electoral landslide and voters’ dissatisfaction with the previous Government.

All this points to:

(was that actually done?) Pre-defining before the election which key policy actions can already be moved forward without new large-scale primary powers, and use all the available devices of varying existing powers and regulations without months of delay.

Getting on with a total financial review to be able to rebase spending estimates rapidly.

Meanwhile obtaining financing agreements with the private sector or public-private consortia to get new projects under way, again without months of delay.

Doing a final check of what should be the first and (probable) second years’ legislative priorities, to progress once Parliament gets going fully in the autumn.

The latter topic assumes that the new Parliament will be allowed to have a summer recess, although during the similar critical years after the Second World War, the Attlee Government had intensive Sessions including late evening sittings (for which London Transport ran Parliament night bus services for MPs, Lords, and staff at Westminster!).

However it is at least possible that Departments targeted with vital early actions may have to put strict limits on holiday-taking until initial regulations/powers/simple Bills are drafted and under way, and/or all financial information lurking in departmental corners has been hoovered into a Comprehensive Spending Review. The Office of Budget Responsibility will be busy throughout – its last (April 2024) report suggested borrowing was £1.2 billion (6.3%) higher than the March forecast profile. “These data remain provisional at this time of year, in particular for departmental spending which is often subject to large revisions.”

High Hopes

Labour has already been on the front foot with a desire to reset relationships and to get on:

Friday 5th July: The King appointed Sir Keir Starmer as Prime Minister and First Lord of the Treasury. He began naming his Cabinet, followed by Ministers over the weekend and early week. Some experts were called in as Ministers to ensure better decision making, including Lord Peter Hendy (later named as Rail Minister).

Weekend 6-7th July: PM and colleagues met the leaders of the devolved nations in their home capitals, in Edinburgh, Belfast, and Cardiff, then the Northern and Midlands mayors, including Lord Ben Houchen (the remaining Conservative Northern mayor).

Home Secretary, Yvette Cooper, promised action within weeks on Border Security.

Monday 8th July: Chancellor Rachel Reeves announced planning reforms and major changes to housebuilding and green energy policies, including bringing back compulsory housebuilding targets and lifting a ban on on-shore wind farms.

Tuesday 9th July: Parliament began and MPs were sworn in. The Prime Minister then headed to Washington for NATO’s 75 th events, and to meet European leaders there, and the US President and his senior team.

The ‘Levelling-Up’ element was ‘tippexed-out’ at the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), which reverted to its former name, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG).

Deputy Prime Minister and Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, Angela Rayner, held a No.10 meeting with local government leaders to discuss resetting the relationship between central and regional governments. It marked the start of establishing Local Growth Plans, urged identification of local specialisms and with the door open to areas who want to take on devolution for the first time.

She said “We have a plan to power up Britain, delivering growth in every corner of the country, with a Take Back Control Act empowering mayors and giving people control over what matters to them. We will rebuild local government, with integrated, long term funding settlements to local leaders…”

Wednesday 10th July: Transport Secretary Louise Haigh said her department’s new motto is “move fast and fix things… Growth, net zero, opportunity, women and girls’ safety, health – none of these can be realised without transport as a key enabler.”

Her five strategic transport priorities are:

Improve performance on the railways and drive forward rail reform.

Improved bus services and grow usage across the country.

Transform infrastructure to work for the whole country, promote social mobility and tackle regional inequality.

Deliver greener transport.

Better integration of transport networks.

Thursday 11th July: Energy Secretary Ed Miliband announced a shift towards greener energy sources, by blocking progress towards more North Sea oil and gas licences.

On Wednesday 17th July, there was the King’s Speech, with a list of 40 Bills to be progressed.

We have listed these actions (not all of them!) to illustrate the scale of (presumably co-ordinated) policy statements across the spectrum, amongst which planning and transport strategies feature. All are early building blocks towards the core Labour objective of stronger economic growth, and a better human environment.

Wish You Were Here

There will be some tensions with regulatory changes, as a greater presumption in favour of investment such as housing development and on-shore wind farms will be resisted in some local areas.

Labour will wish to change the national planning rules quickly, to stimulate private sector commitment, and so that devolution with strengthened local government focuses on the wins which the rule changes will encourage. These actions will be strengthened by a Planning & Infrastructure Bill, and an English Devolution Bill.

Creation of further New Towns is a Labour manifesto target, along with potential release for housing of ‘grey’ lands – poor quality green belt – and these will require further, targeted transport capacity. We can expect Homes England and equivalent bodies to need to gear their outputs to the new national objectives.

However everything depends on clear Government knowledge about what is affordable to do, and local government willingness to work with the grain of Labour priorities and have faster planning consultation and approvals – with the initial higher cost of accelerating planning actions being underwritten by Government.

Heavyweight mayors in the form of Andy Burnham (Greater Manchester) and Sadiq Khan (Greater London) already have their own lines into Whitehall, Westminster, and Nos.10 & 11.

The development sector will also benefit from stimulus to move faster towards conversion of land holdings into new construction, and to collaborate with local authorities on delivering local growth plans once those are devised and authorised.

There is no shortage of ideas and influencing reports from multiple organisations, now winging their way into the Labour Government and its advisers. For example, the University of Manchester has published its ‘what-needed’ assessment of how best to harness planning changes to achieve lasting and worthwhile outcomes.

The importance of the overlap between planning and transport has been highlighted by public transport advocates such as the Campaign for Better Transport. They have pointe out the risks of new housing in locations with no prospect of being connected by sustainable transport. They argue that new developments should be designed and located with a view to facilitating the development of new active travel and public transport links, which would improve connectivity for existing communities, as well as the enhancement of existing links.

Money

Underpinning all Government actions will be the availability (or lack) of new sources of funding, even though the UK has a annual trillion pound expenditure. Back in December 2023 Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves were warning about UK’s limited financial headroom.

The Government may insist on opening up all the books and to see what other naughties, and large £ noughties, might lurk within. That could lead to a later autumn budget, with the new government’s spending plans waiting till then unless some critical matters required urgent attention. Finding enough short term stimuli to get the economy going is Labour’s biggest single challenge.

Foreseeable new Treasury costs during the second half of 2024, measured in £10 billion-worths, include compensation for sub-postmasters, the NHS blood contamination scandal, shortfalls in national flood defences, and re-financing of energy and water supply businesses. The latter includes possible renationalisation of Thames Water after the collapse of its parent company.

Careful with that Axe Euston

Capital projects of all sorts may wait in the queue behind those. Construction cost inflation has soared since Covid, and many projects are now under-costed. There is a risk that much desired spend has to move towards 2029-34 (which happens to be a financial control period for rail investment as well as a possible second parliamentary term for Labour), along with a hope that the national economy will have picked up in time for the next round of campaigning and manifestos.

The Chancellor announced on 29th July some immediate measures to save £22 billion in the current year, including road and rail projects. Rachel Reeves said: “The spending audit has revealed nearly £800m of unfunded transport projects that have been committed next year. So the Transport Secretary will undertake a thorough review of all these commitments. As part of that work, she has agreed not to move forwards with projects that the previous government refused to publicly cancel, despite knowing full well they were unaffordable. That includes proposed work on the A303 [Stonehenge Tunnel] and the A27 [Arundel bypass], and she will also cancel projects in the “Restoring our Railways” programme which have not yet commenced. If we cannot afford it, we cannot do it.”

Allons-y

Transport is an enabler for economic growth, though it has historically been in a second tier of national priorities below Health, Defence, Education, and Social Security. However it is now important enough for Labour to allocate it Parliamentary time for four Bills:

Better Buses Bill – Reform to bus services and franchising, including allowing local control and supporting public ownership.

Passenger Railway Services (Public Ownership) Bill – A bill to amend rail legislation to make public sector operation the default.

Railways Bill – A bill to reform rail including establishing GBR and more integrated railway operations, with a renewed focus on passenger service and freight growth.

High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester) Bill – Continuation and adaptation of the (formerly HS2) Hybrid Bill, to expand powers for building rail infrastructure between Crewe and Manchester.

Subsidy shortfalls are faced by buses, and the main parties are pledged to keep their funding going. Policies supporting more action on net zero, better service levels, and support for other Active Travel and integrated travel policies were all pushed with increasing scales of support by Labour, LibDem, and Green Parties before the election.

All depends on a supportive funding climate and regulatory changes, including stronger powers for local authorities to oversee or directly control the local bus and alternative travel networks. With the slow pace of rail schemes, early changes on transport capacity and connectivity also point to high priority for bus initiatives, so that the Better Buses Bill is likely to be in the first year’s legislative round.

It is already recognised that much can be achieved towards the objective of a ‘Great British Railways’ (GBR) within existing legislation, whilst the ‘Williams-Shapps’ proposals for rail reform had broad all-party support prior to the election. Given the scale and complexity of changes being sought for the railway sector, the current pre-legislative scrutiny will need to continue, to provide parliamentarians and experts across industry the opportunity to review and test the legislation in draft.

There will also be immense pressure on Parliamentary time, and it is unlikely that 40 Bills could all be made law within one Session of Parliament. So it is possible that mainstream railway legislation will arrive in two phases, with the first (and easier) one being an early Public Ownership Bill. Meanwhile, better railway operational performance is an even earlier political priority for the Transport Secretary, with Avanti having already been highlighted. Having the main ‘GBR’ Bill start later in the first year’s Session or at the beginning of the second, could help matters all round. It might also allow progress with negotiations on railway productivity, instead of existing pay and conditions being ‘baked in’ to the new legislation.

Rail expert Roger Ford has summarised the need as:

“commentators are getting excited about the immediate prospects for their pet projects with the change of government, but the over-riding priority must be to restore a boringly reliable and dependable railway that customers – passenger and freight – trust and give Government confidence that our industry can deliver. Then we can get on with restructuring – a better word in my book than reform.”

The High Speed Bill of course provides a renewed breath of life for improved railway capacity and connectivity within the Midlands and the North, on planning terms likely to be more favourable to the aspirations of the Northern Powerhouse group. The complementary HS2 Phase 2 review activity continues under Sir John Armitt’s chairmanship, whilst Transport Secretary Louise Haigh is actively trying to find a pragmatic solution to the funding gap which has caused Old Oak Common to become the temporary HS2 London terminus.

Continuation of this and any of the alternative ‘Network North’ schemes espoused by the Conservatives last October, which provided a unfunded spending gloss as far as Wales and the West Country, will still depend on the availability of actual funding – and/or third party funding support. The strength of local and regional support to continue with those schemes will be an important litmus test.

There will be significant top-level rail and public transport skills embedded within the DfT and the revised rail industry, with four influential ‘top delivery team’ individuals with close formal working links:

Lord (Peter) Hendy, a long-serving Transport Commissioner in London, is now a Minister of State (Rail Minister) at the DfT, overseeing all rail matters.

Andrew Haines is still the Chief Executive of Network Rail (where Peter Hendy was previously his chairman), and has also been overseeing the Great British Railways Transition Team.

Alex Hynes has already moved from being Managing Director (MD) of Scotland’s Railway (where he ran an integrated operation of infrastructure and rail services), to become the Director General, Rail Services at DfT – this was a move approved by the previous Government.

Robin Gisby, another senior rail industry director and formerly MD, Network Operations, at Network Rail, has for some years led the DfT Directorate which manages the DfT ‘Operator of last resort’ Holdings Limited (DOHL) for failed rail franchises – this is likely to be expanded substantially in the short term.

Round and Around

On roads, both main political parties vied with each other on potholes to be repaired – itself a statement on the current inadequacy of funding for local authorities. They also gave headline statements on helping the car user – Labour’s manifesto said: “Cars remain by far the most popular form of transport. Labour will maintain and renew our road network, to ensure it serves drivers, cyclists and other road users, remains safe, and tackles congestion”.

In practice, we can expect HM Treasury to implement road duty on low carbon vehicles to protect its tax revenues! Roads investment will be constrained so long as taxes on transport energy use are held down – so will be a function of Treasury’s ability to raise new borrowing to help grow the economy – just as for rail investment. Further delays can be expected for projects such as the Lower Thames Crossing. The election heightened political arguments about net zero objectives, and the roles of road pricing and emission control. It will be important to track Labour’s progress on these topics as a Government.

Making shipping and aviation more sustainable are political targets, particularly in relation to bio-fuels. Hydrogen has also been mentioned, although its applicability to most forms of transport is disappearing like a free floating balloon. However no general policy was identified by any party about tackling trunk lorry emissions. Is this an elephant in the room over the lifetime of a Labour government which might be in existence for a decade? An expanded role for rail freight has been advocated by the Rail Freight Group. A pledge to grow rail freight by 75% by 2040 has been Government policy since December 2023. In its manifesto, Labour had proposed a “duty” to promote the use of rail freight.

Sysyphus

In conclusion, the nature of national elections is that multiple topics will receive only passing coverage in manifestos. However Labour gave extensive thought to its early planning and transport intentions, and can promote its policies with electoral stability – but without the funding certainty to deliver much new in capital investment, and requiring careful management of revenue spend.

The risk is that the next five years see a longing for action which is only afforded in small increments, with economic growth largely dependent on motivating communities and businesses through some existing policy levers and funding mechanisms.

The post The governing realities for Labour in power, & what it means for planning and transport appeared first on London Reconnections.