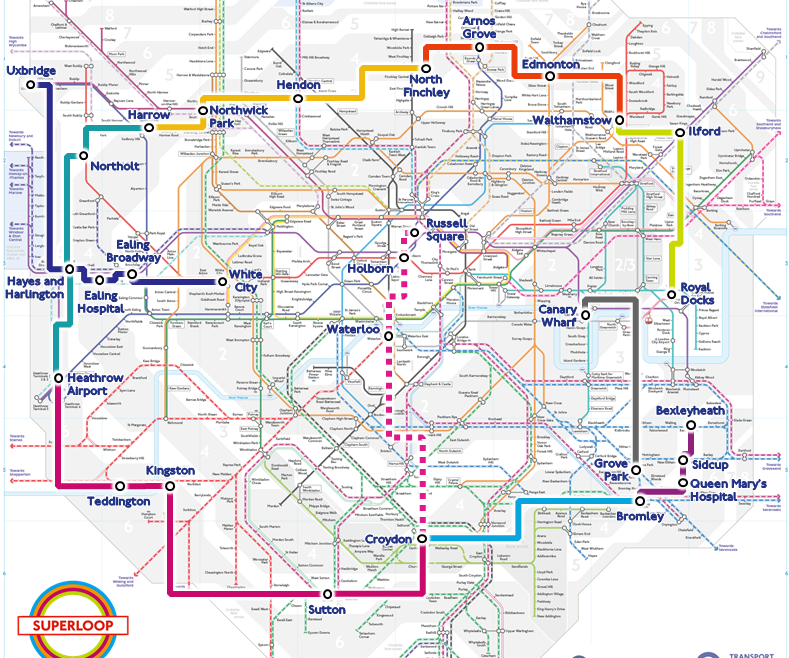

Someone at City Hall found the box of crayons. On the 28th of March, Transport for London unveiled a map of a new transport proposal. It featured a colour scheme to rival the New Jersey Transit disco stripes, a stylised loop around outer London, and a name that brings a certain ABBA song to mind. But what exactly is a Superloop, and will it get people around more efficiently than the similarly-named subterranean traffic jam?

A bundle of bus routes

Superloop is a bus. More specifically, it’s a proposed network of frequent limited stop bus routes, including seven orbital routes almost completely encircling outer London. Two of those are existing services: The half-hourly X26 from Croydon to Heathrow which TfL intend to double in frequency, and the X140 from Heathrow to Harrow. These could be a big element of Superloop – plenty more on Heathrow buses needs sorting, but this is a good start.

TfL plan to consult on the third later this year, namely the X183 from Harrow to North Finchley. The other four are purely lines on a map for now; a Diamond Geezer post gives some educated guesses on how they might look. They’ll certainly be less of a neat circle than the graphic implies.

They’re joined on the map by two existing radial routes, likely thrown in to create a more substantial day one network. The limited stop 607 from White City to Uxbridge, a frequent workhorse of the Uxbridge Road, and peak express X68 from Russel Square to Croydon. The disconnected line from Canary Wharf to Grove Park represents the X239, the express element of the proposed Silvertown Tunnel bus network

These ten routes are all packaged together to create something new and shiny for Outer London in advance of the expansion of the Ultra-Low Emissons Zone across Greater London. The press release is explicit about this:

“The Superloop is the jewel in the crown in our plans to strengthen alternatives to the private car ahead of the ULEZ expanding London-wide and is a game changer for outer London.”

This has provoked some cynicism and some playground wordplay – but one might also let a little gimmickry slide if it helps address the considerable impact of status quo tailpipe emissions.

We also recently looked at Mayor Khan’s initiative to breakout the anonymous Overground lines into their six constituent names and map identities. This alongside the superloop proposal could demonstrate a meaningful commitment to London’s suburb-to-suburb connections.

Superloop schematic routes superimposed on the Tube Map. Jesse Feld

London’s Green Line suburban buses

Few things are entirely new. Boris Johnson had promised a similar network in his 2008 transport manifesto. His idea of “a distinct mode of transport… with coach style vehicles and a limited number of stops” recalls London General Omnibus Company’s ‘Round-London’ routes — three bus routes which plied London’s fringe through the late 20th Century.

Green Line Network Map 1977. London Country Bus Services

The first of these began in 1953. The 725 ran from Gravesend to Windsor via Dartford, Croydon, and Kingston. By the seventies a sister route 726 ran via Heathrow. In the North and West, the 724 and 727 were introduced in the late sixties, linking Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire Towns beyond what became Greater London.

The 724 lives on as an hourly regional bus between Harlow, St Albans, Watford and Heathrow. Within Greater London meanwhile, an hourly 726 staggered on. In 1991, its abbreviated Heathrow to Dartford route was proposed for withdrawal and taken on by London Transport. LT in turn tried to jettison the route in 1997. They relented but cut the Eastern terminus back to Bromley. In 2005 it became the X26, cut further back to Croydon and with stops limited to town centres a mile or two apart.

So if their fifty-plus-year survival is a success story for fast orbital buses, it’s a distinctly moderate success. Both remain very much low-frequency buses that get stuck in traffic. As then Mayor Ken Livingstone described the 726 in 2004:

“Basically, it looks like it has been designed to go through every congestion traffic spot in south London, from one end to the other.”

A perennial difficulty of planning bus routes is that popular destinations, like the town centres absorbed into London suburbs, are typically congested parts of the road network. The problem is worsening traffic on London’s roads, with bus speeds declining over the past decade.

Green Line 1977 routes vs Superloop routes. Martha Lauren

Today’s X26 takes anywhere from 75 to 140 minutes to cover twenty miles. On journeys like Croydon to Kingston, a relatively circuitous rail trip via Clapham Junction is faster. Given the problem of speed and punctuality, when service was increased to half-hourly in 2008 TfL observed “benefits to a relatively small number of passengers”.

The optimist might hope that the proposed fifteen minute frequency makes a bigger difference because schedule adherence matters less to the passenger at high frequency. We shall have to see.

The X140: Three bus routes and no money

If half an hour seems like a long wait, it took until 2019 before another fast orbital bus route arrived: The X140’s alliterative route between Harrow, Hayes, Harlington, and Heathrow. It’s something of a different beast: A high frequency route from the outset, making thirteen stops over a more operationally manageable eleven miles.

It was also created without a significant budget by reallocating existing bus service hours. The Superloop press release only mentions £6 million of funding, not enough to meaningfully add service. So unless a good deal more materialises, the X140 is a good case study in what we can expect of future routes.

Previously, the 24-hour local route 140 provided local service every 6-8 minutes along a thirteen-mile route between Harrow Weald, Harrow, Northolt, Hayes & Harlington, and Heathrow Central. In 2019, it was split into three overlapping routes:

A shorter 140 from Harrow Weald to Hayes & Harlington, every 8-10 minutes.

The X140 from Harrow to Heathrow Central, every 12 minutes.

Night bus N140, making local stops from Harrow Weald to Heathrow Central.

Map of 140 and parallel routes. Martha Lauren

Local service through the sparsely populated airport hinterland was duplicated by routes 90 and 278, allowing the 140’s southern end to be cut. The performance benefits of a shorter route and separation from airport traffic meant frequency could also be reduced without much impact on passengers’ actual waits. Thus resources were released for its express counterpart.

Carving out service hours by rationalising local routes is a decent idea. It was, for example, an element of Vancouver’s successful Rapidbus network. And it seems to have worked in West London. Making fewer stops and skipping the West Harrow deviation, the X140 shaves ten minutes off a previously hour-long trip from Harrow to Heathrow. TfL claim a 10-15% increase in weekday demand — they don’t show their working, so some of that may be abstracted from other routes.

Still, shuffling around service hours feels like an underwhelming version of the heralded Superloop. And with the majority of bus trips in outer London being local in nature, it’s not certain that the same will always suit local travel patterns. Absent new funds, it’s a corridor-by-corridor question whether each part of the grand loop proves beneficial to passengers.

Paying twice

Likely boosting the X140’s passenger numbers is the considerable fare premium for travel between Hayes and Heathrow on the faster Elizabeth Line – a single fare of £7 which, because this is London, doesn’t include any connecting bus.

The lack of free interchange between rail and bus is a British peculiarity. While daily commutes outside Zone 1 benefit from decent value period Travelcards including both bus and rail, there is no equivalent day cap. Hence many outer London passengers have a strong price incentive to stick to buses, unless rail covers their entire journey.

This is economically bizarre. Reducing rail service at the outer ends of lines is easier said than done, meaning there’s plenty of spare rail capacity in London with a marginal cost close to zero.

The orbital Superloop routes would rightly complement a mostly radial rail network. Convenient interchange between the two would enable faster suburb-to-suburb trips utilising existing capacity. The fact that current fares discourage interchange between modes is a barrier to a more efficient transport network.

…at the front door

Superloop route 5 bus livery

Also contrasting with international best practice is the use of double deck buses, and fare enforcement by means of everyone filing through the front door. Enhanced bus routes elsewhere typically feature articulated vehicles that passengers can board through any door, with fares enforced by occasional inspections.

A 2017 London Assembly transport committee report suggests that “articulated buses might be the best option for express routes”, noting their high capacity, easy access, and reduced boarding times. The tight corners of Central London challenged the bendybuses of the 2000s, but straighter routes along Outer London’s main roads could prove a better fit.

Another option would be to adopt long three-axle double deckers like the ADL Eviro500. Examples in Singapore and Berlin feature three doors and two staircases to improve passenger flow—much like a New Bus for London, but with a less cramped interior.

North American cities have been implementing all-door boarding measures in recent years – this has reduced reduced travel times by 8% on Seattle’s Aurora Avenue corridor. Despite anecdotes about fare evasion, San Francisco’s switch to all-door boarding saw no significant change in the rate of non-payment.

TfL research on New Bus for London boarding times was more lukewarm, observing little difference on account of the all-door boarding that was in place up to 2019. Cashless operation already means reasonable boarding times in London, and any further benefit was likely limited by the cramped interiors and staircases.

This leaves all-door boarding the preserve of Central London bus routes 507 and 521, which continue the practice “to clear some of London’s busiest stops”. The two are remnants of the Red Arrow network, single deck routes introduced in the 1960s to efficiently move peak crowds over short Central London corridors. Both of these routes are due to be withdrawn following a post-pandemic decline in their core market of white collar commuters. Absent someone to champion best practice bus operations, boarding a London bus at the rear door is set to become a lost art.

The Grove Park to Canary Wharf Route

At least one segment of Superloop requires completion of a separate project, namely the Grove Park to Canary Wharf route.

If this route starts before Silvertown tunnel completion in 2025 (it likely won’t), then it will be limited to single deck buses due to the Blackwall Tunnel. This low tunnel led to the decades of poor economics for the 108, which currently runs between Lewisham and Stratford, due to the many single deck buses required for sufficient capacity.

Otherwise, the new Silvertown Tunnel and the potential for double deck buses radically improves the economics, and it’s potentially useful for to relieve the DLR between Canary Wharf and Stratford.

The probable route will be via:

Canary Wharf

Canning Town station

New City Hall (which could be the real reason for the entire route, as the new seat of London government it is such a pain to get to via public transport)

North Greenwich station (on the Jubilee line) then the Silvertown Tunnel

Westcombe Park station (on the Greenwich suburban line)

Blackheath station (on the Bexleyheath suburban line)

Grove Park Station (on the Orpington and Bromley North Branch suburban line),

What Superloop isn’t

It’s certainly no Superbus – the branding applied in the 1990s to North Leeds’s pioneering guided bus corridor and the aggressive bus priority it enjoyed. Looking at Superloop publicity, alongside current limited stop routes, suggest a gradual roll out of modest changes to particular corridors: this is neither best practice rapid bus service, nor a comprehensive rethink of London’s bus network.

Modest changes are no bad thing. A bus network that’s gradually improved through the 21st Century is a large element of Outer London maintaining sub-50% private car mode share. And there remains the possibility of future funding to enable a more promising orbital network with higher frequencies.

London was a pioneer of smart payment. The introduction of the Oyster card in 2003 and fully cashless buses in 2014 helped speed the bus network. But with declining bus speeds due to congestion in more recent years, London’s resistance to international practices like all-door boarding (where helpful) and lack of recent investments in bus priority lessen the time savings that new limited stop buses can accomplish.

The post Superloop: Analysis, hopefully not paralysis appeared first on London Reconnections.