As the Overground has grown, calls have increased to provide its sub-lines with clearer identities of their own. Behind the scenes, TfL have been working to do just that. Those new identities have now been revealed.

The Orange

“But I thought it was all going to be orange.”

These were the words that ensured that the London Overground, when it launched in 2007, would be a single colour – orange – on the Tube map. They were uttered by then-Mayor Boris Johnson in his office at City Hall.

TfL’s original plan had been to give the lines more of an identity somehow. Perhaps not in name – not in the early stages when there were less sections directly under their concessionary control – but at least in terms of colour.

Picking colours had always traditionally come towards the end of a new line’s design stage though. And until then they still needed to be indicated in some way on the various maps and documents that passed through people’s desks. This had been the case with the new sections of Overground that TfL had managed to pluck from the control of the DfT. Most notably the North London Line (NLL), which had been run into the ground by its previous post-privatization operator, Silverlink. Silverlink’s operators had never wanted it, but it had been bundled with other sections of railway that they did want. So they had no choice. It had been an unloved and under-developed line, until TfL finally secured its control.

With the support of Olympic funding, the redevelopment of the NLL and the East London Line (ELL) had begun. Indeed it was perhaps the ELL that had caused the “holding” colour for the new combined operation to be orange – it had previously appeared on maps as a sort of muddy orange, on the map, bordering on brown.

Whatever the reason, it turned out that day in the Mayor’s office that Boris Johnson had assumed the colour was deliberate. And final.

So that’s what it became. The Overground would all be orange. It wasn’t a bad colour, after all. It stood out. It passed accessibility. It certainly made a statement and (rather handily) it meant no one had to repaint or update a lot of panels at various ELL stations. The colour there was already a close enough match in the right light (take a look at the panels on the platforms at Wapping to see the evidence of this).

The Turquoise

It would be easy to be outraged that the colour for the Overground was decided in such a frivolous way. But the reality is that Tube colours – and names – have always been picked on more of a whim than most people think.

For many years, for example, a story circulated that the colour of the Waterloo & City line was chosen because it matched the dress of a legal secretary who had worked on its transfer over from British Rail. She had worn it to the project party to celebrate the completion of the process, the tale went, and the project team thought she was rather attractive in it. So when they saw something close to that colour, it was fresh in the memory and they went with that.

It’s a story that has the ring of a pub tale about it. A railway myth. It reads too well and too conveniently, with the exact hint of low-level workplace sexism one would expect to find in a story that circulated among older railwaymen over beers after work.

So many years ago, we actually embarked on a mission to try and track the origins of this story down. After all, we thought, there’s enough clues within it that it’s possible – with a bit of lateral thinking and access to the right records – to at least disprove it. Especially as TfL were unable to confirm the origins of the colour themselves. If nothing else, we could at least kill off this myth.

Which is how, some weeks of detective work later, this author found himself chatting on the phone to a senior city lawyer who, with some amusement, confirmed that the Waterloo & City line was turquoise because of her.

The real story was close to the myth, she explained. It just needed the sexism stripped out of it. That was the part that had twisted the story over the years. As a junior lawyer she had worked as part of the transfer team. It had actually been one of her first jobs in transport law. And when it came time to pick the colour of the line, her colleagues had offered her the honour of doing so. Partly as a thank you for her work on what was a complex legal project. Partly because they thought it would be a nice way of marking the beginning of her career. Nobody else would know that was why it was that colour. Nobody would likely ever ask. But it would be a fun reminder for her, they said, so why not?

She agreed, and was shown a selection of pre-approved colours by the London Underground design office. Any of them would work, she was told. So just pick one. Noticing that one was quite close to turquoise – her favourite colour – she simply chose that.

Did she have a dress in that colour?

Of course, she confirmed. It was her favourite colour. But she doubted any of the team would ever have seen her in it. She wasn’t in the habit of partying with random, older male colleagues.

The new names and colours

As the two stories above show, line colours – and names – have always been somewhat arbitrary and random. So whatever names TfL had opted to use for the newly split Overground – and whatever colours – could never be “wrong”. Because there have never been any rules to break. Similarly, Londoners will always shorten any name that a line acquires to make it roll off the tongue quickly.

But this doesn’t mean that line names don’t matter. Or rather, that they can be made to matter if they are done right. Naming a line is a rare opportunity.

In the novel Going Postal, the fantasy author Terry Pratchett described a world where communication took place through a network of semaphore towers known as ‘The Trunk’. Along the Trunk, occasionally, would pass messages that were never officially recorded. Those messages, it turned out, were names. Names of people who had died in service to the network and which now circulated perpetually on it.

“You know they’ll never really die while the Trunk is alive.” The character of Moist von Lipwig mused. “it lives while the code is shifted, and they live with it, always going home.”

“A man is not dead while his name is still spoken.”

Cities are not men. But they are alive. They live through the people who call them home and through the events they experience. Both good and bad. People move on, times change but on some level the city… on some level London remembers. And that is what binds us, as Londoners, together. It is our most common ground.

The names and colours of the new lines are below, alongside the reasons for each one. We pass no opinion on them. We have no doubt many people will. And that’s fine. What we will say, is that they all refer to something about this city – our city – that does deserve to be remembered.

Visibility matters, and there is nothing more iconic, and visible, than the Tube map.

The Lioness line: Euston to Watford Junction. The Lioness line, which runs through Wembley, honours the historic achievements and lasting legacy created by the England women’s football team that continues to inspire and empower the next generation of women and girls in sport. It will be yellow parallel lines on the map.

The Mildmay line: Stratford to Richmond/Clapham Junction. The Mildmay line, which runs through Hoxton, honours the small charitable hospital in Shoreditch that has cared for all Londoners over many years, notably its pivotal role in the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s, which made it the valued and respected place it is for the LGBTQ+ community today. It will be blue parallel lines on the map.

The Windrush line: Highbury & Islington to Clapham Junction/New Cross/Crystal Palace/West Croydon. The Windrush line runs through areas with strong ties to Caribbean communities today, such as Dalston Junction, Peckham Rye, and West Croydon, and honours the Windrush generation who continue to shape and enrich London’s cultural and social identity today. It will be red parallel lines on the map.

The Weaver line: Liverpool Street to Cheshunt/Enfield Town/Chingford. The Weaver line runs through Liverpool Street, Spitalfields, Bethnal Green and Hackney – areas of London known for their textile trade, shaped over the centuries by diverse migrant communities and individuals. It will be maroon parallel lines on the map.

The Suffragette line: Gospel Oak to Barking Riverside. The Suffragette line celebrates how the working-class movement in the East End fought for votes for woman and paved the way for women’s rights. The line runs to Barking, home of the longest surviving Suffragette Annie Huggett, who died at 103. It will be green parallel lines on the map.

The Liberty line: Romford to Upminster. The Liberty line celebrates the freedom that is a defining feature of London and references the historical independence of the people of the borough of Havering, through which it runs. The name references the borough’s motto and historical status as a royal liberty, an area that traditionally had more self-governance and autonomy. It will be grey parallel lines on the map.

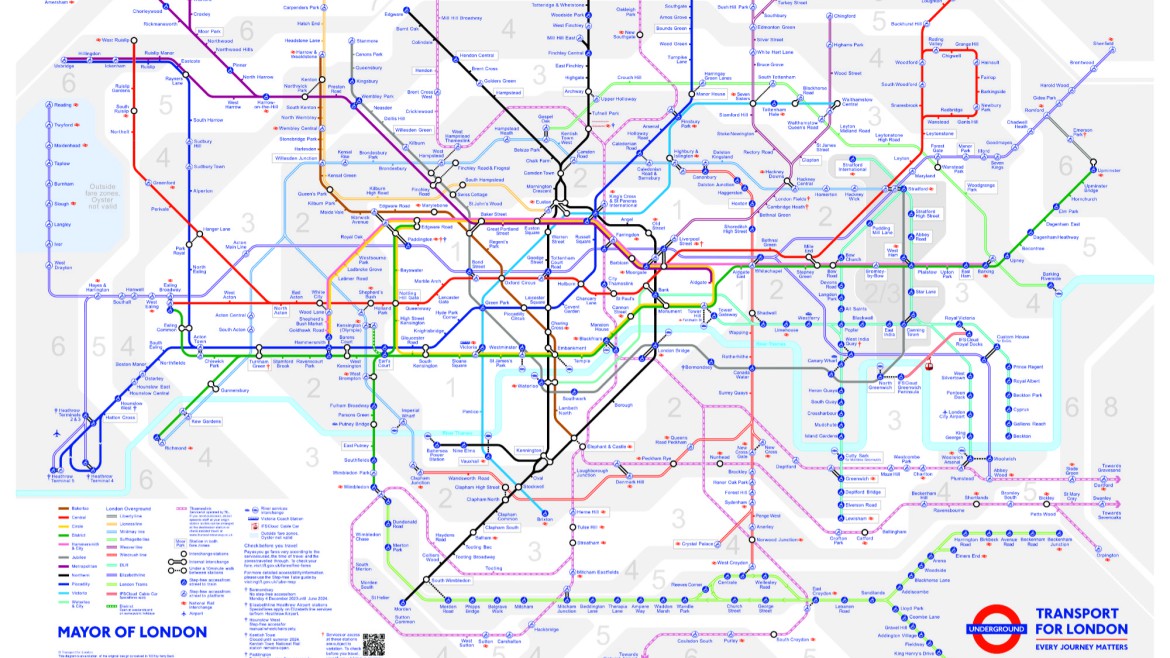

The Autumn 2024 Tube map, showing the new line colours

We had previously looked at the evolution of the devolution of railway lines to London Overground, their lengthy and cumbersome official TfL line identifiers, and their commonly used line names. As well as the 2023 TfL process and criteria for Overground line renaming and colour selection. We then ventured a guess at the potential line names and colours – we were off on all of them, although we picked some of the new line colours correctly.

The post The Big Split: Overground Line Names appeared first on London Reconnections.

502 Comments

https://biotpharm.com/# get antibiotics quickly

buy antibiotics from canada buy antibiotics online over the counter antibiotics

over the counter antibiotics: buy antibiotics online – Over the counter antibiotics for infection

get antibiotics quickly: over the counter antibiotics – get antibiotics quickly

http://pharmau24.com/# Buy medicine online Australia

Pharm Au 24 Licensed online pharmacy AU Medications online Australia

Ero Pharm Fast: ed med online – Ero Pharm Fast

Online medication store Australia: Pharm Au24 – Medications online Australia

buy erectile dysfunction pills ed medicines online cheapest online ed treatment

antibiotic without presription: antibiotic without presription – get antibiotics quickly

buy antibiotics buy antibiotics online buy antibiotics

Buy medicine online Australia: PharmAu24 – Licensed online pharmacy AU

buy antibiotics for uti buy antibiotics from india buy antibiotics

https://eropharmfast.com/# п»їed pills online

Buy medicine online Australia: pharmacy online australia – Online medication store Australia

buy antibiotics online BiotPharm cheapest antibiotics

buy antibiotics: BiotPharm – get antibiotics without seeing a doctor

buy antibiotics from india buy antibiotics for uti buy antibiotics from india

http://pharmau24.com/# online pharmacy australia

pharmacie en ligne: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne fiable

commander Kamagra en ligne kamagra oral jelly achat kamagra

Acheter du Viagra sans ordonnance: Acheter du Viagra sans ordonnance – commander Viagra discretement

pharmacie en ligne pas cher: acheter medicaments sans ordonnance – vente de mГ©dicament en ligne

vente de mГ©dicament en ligne: Cialis pas cher livraison rapide – Cialis pas cher livraison rapide

Cialis générique sans ordonnance: Cialis générique sans ordonnance – Acheter Cialis

https://pharmsansordonnance.com/# pharmacie en ligne livraison europe

Pharmacies en ligne certifiees Pharmacies en ligne certifiees Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable

Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h: prix bas Viagra generique – Quand une femme prend du Viagra homme

Pharmacies en ligne certifiees: commander sans consultation medicale – pharmacie en ligne pas cher

acheter Cialis sans ordonnance: traitement ED discret en ligne – cialis prix

Acheter du Viagra sans ordonnance Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h commander Viagra discretement

Cialis generique sans ordonnance: vente de mГ©dicament en ligne – commander Cialis en ligne sans prescription

cialis generique: cialis sans ordonnance – Acheter Cialis

Viagra générique en pharmacie: Viagra sans ordonnance livraison 24h – Viagra 100 mg sans ordonnance

http://ciasansordonnance.com/# cialis sans ordonnance

kamagra en ligne kamagra oral jelly kamagra en ligne

Acheter du Viagra sans ordonnance: Viagra sans ordonnance livraison 48h – acheter Viagra sans ordonnance

achat kamagra: kamagra livraison 24h – achat kamagra

Acheter Cialis: pharmacie en ligne france pas cher – Acheter Cialis

livraison discrete Kamagra kamagra en ligne commander Kamagra en ligne

Viagra generique en pharmacie: commander Viagra discretement – commander Viagra discretement

viagra en ligne: viagra en ligne – livraison rapide Viagra en France

https://ciasansordonnance.shop/# traitement ED discret en ligne

kamagra gel: kamagra livraison 24h – acheter Kamagra sans ordonnance

Cialis generique sans ordonnance cialis generique cialis prix

acheter kamagra site fiable: achat kamagra – commander Kamagra en ligne

pharmacie en ligne france pas cher: commander Cialis en ligne sans prescription – cialis generique

Pharmacies en ligne certifiees acheter medicaments sans ordonnance pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

acheter medicaments sans ordonnance: pharmacie en ligne – Pharmacie Internationale en ligne

cialis prix: Cialis sans ordonnance 24h – cialis prix

Acheter du Viagra sans ordonnance: Prix du Viagra 100mg en France – commander Viagra discretement

https://pharmsansordonnance.com/# pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

commander sans consultation medicale: pharmacie en ligne – Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe

acheter medicaments sans ordonnance pharmacie en ligne pas cher Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable

pharmacie internet fiable France: Pharmacies en ligne certifiées – pharmacie en ligne livraison europe

pharmacie en ligne sans prescription: commander sans consultation medicale – Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable

commander sans consultation medicale: commander sans consultation medicale – Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable

achat kamagra: kamagra en ligne – kamagra pas cher

kamagra gel kamagra oral jelly acheter Kamagra sans ordonnance

https://ciasansordonnance.shop/# cialis prix

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: Pharmacies en ligne certifiees – pharmacie en ligne france fiable

acheter kamagra site fiable: kamagra en ligne – commander Kamagra en ligne

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance: acheter médicaments sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

Acheter Cialis acheter Cialis sans ordonnance cialis prix

pharmacie en ligne france fiable: Pharmacie sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

pharmacie en ligne fiable: kamagra livraison 24h – commander Kamagra en ligne

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

Viagra vente libre pays viagra sans ordonnance Viagra generique en pharmacie

kamagra livraison 24h: Kamagra oral jelly pas cher – acheter Kamagra sans ordonnance

kamagra oral jelly: pharmacie en ligne – kamagra gel

Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h pharmacie internet fiable France п»їpharmacie en ligne france

livraison discrete Kamagra: commander Kamagra en ligne – kamagra livraison 24h

Acheter Cialis: cialis prix – commander Cialis en ligne sans prescription

acheter Kamagra sans ordonnance kamagra oral jelly commander Kamagra en ligne

https://kampascher.com/# acheter Kamagra sans ordonnance

livraison rapide Viagra en France: Viagra vente libre allemagne – viagra en ligne

Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h: acheter medicaments sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

pharmacie en ligne sans prescription pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

kamagra 100mg prix: achat kamagra – kamagra pas cher

prix bas Viagra generique: Acheter du Viagra sans ordonnance – prix bas Viagra generique

pharmacie en ligne pas cher Pharmacies en ligne certifiees vente de mГ©dicament en ligne

http://viasansordonnance.com/# livraison rapide Viagra en France

Viagra sans ordonnance 24h: livraison rapide Viagra en France – Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h

Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france fiable

kamagra livraison 24h kamagra 100mg prix Kamagra oral jelly pas cher

п»їpharmacie en ligne france: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie

Cialis pas cher livraison rapide traitement ED discret en ligne cialis prix

kamagra 100mg prix: acheter kamagra site fiable – achat kamagra

http://pharmsansordonnance.com/# pharmacie en ligne france fiable

traitement ED discret en ligne Acheter Cialis cialis prix

Cialis sans ordonnance 24h: traitement ED discret en ligne – Cialis sans ordonnance 24h

acheter Kamagra sans ordonnance commander Kamagra en ligne kamagra pas cher

acheter medicaments sans ordonnance: pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

Viagra generique en pharmacie Viagra gГ©nГ©rique pas cher livraison rapide Meilleur Viagra sans ordonnance 24h

commander Viagra discretement: viagra sans ordonnance – prix bas Viagra generique

https://pharmsansordonnance.com/# pharmacie en ligne france pas cher

commander Cialis en ligne sans prescription cialis prix cialis sans ordonnance

acheter kamagra site fiable: achat kamagra – kamagra 100mg prix

commander Cialis en ligne sans prescription cialis prix pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es

Viagra homme prix en pharmacie sans ordonnance: viagra sans ordonnance – Viagra vente libre pays

pharmacie en ligne france pas cher: kamagra en ligne – kamagra oral jelly

kamagra en ligne Kamagra oral jelly pas cher trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie

https://kampascher.com/# pharmacie en ligne france fiable

pilule contraceptive pharmacie sans ordonnance: bequille pharmacie sans ordonnance – amoxicilline en ligne sans ordonnance

farmacia san rocco online: farmacia online cГіrdoba – farmacia mascarilla online

testoviron 250 xanax 1 mg fripass 100 mg prezzo

descuentos farmacia online: se puede comprar vacuna gripe sin receta – se puede comprar clembuterol sin receta

http://pharmacieexpress.com/# soigner conjonctivite sans ordonnance

xylocaina crema: Farmacia Subito – farmacia online preferita

skinceuticals blemish Pharmacie Express huile gomenolee sans ordonnance

farmacia ciudad real online: comprar ozempic sin receta espa̱a Рel salbutamol se puede comprar sin receta

xenical sans ordonnance: medicament sans ordonnance angine – une ordonnance

farmacia online envio gratis farmacia pt online se puede comprar cerazet sin receta

dicloreum 150 compresse prezzo: Farmacia Subito – mascherina ffp2 farmacia online

anti stress pharmacie sans ordonnance: ivermectine crГЁme sans ordonnance – elancyl slim design

atarax sans ordonnance en pharmacie: medicament antidГ©presseur sans ordonnance – peut on acheter la pilule en pharmacie sans ordonnance

https://confiapharma.com/# farmacia online correos

acheter de l’amoxicilline sans ordonnance stimulant puissant pour homme en pharmacie sans ordonnance miroir dentaire pharmacie

lansoprazolo 30 mg 28 compresse prezzo: movicol stick – resolor 1 mg prezzo

pilule bleu en pharmacie sans ordonnance: zolpidem prix pharmacie sans ordonnance Рcr̬me rap

comprar viagra en madrid sin receta: como comprar sildenafil sin receta – la pildora se puede comprar sin receta

prefolic 15 mg dibase 50000 niklod 200

tinset gocce bambini: Farmacia Subito – bivis 40/10

http://confiapharma.com/# farmacia online sant cugat

farmacia online roma: combantrin prezzo – pantorc 40 mg prezzo senza ricetta

farmacia online mascherine impetex crema cosa serve farmacia shop online

farmacia clemente: Farmacia Subito – puntura decapeptyl 3 75 prezzo

commander ozempic sans ordonnance: viagra generique – tadalafil 10mg prix

niklod 200 fiale mutuabile: dibase 25000 – quanto costa la cardioaspirina

farmacia senante actur online mascarillas kn95 farmacia online farmacia andorra online envГo espaГ±a

se puede comprar vimovo sin receta: Confia Pharma – farmacia vitalogy online

http://pharmacieexpress.com/# gingembre et foie

dirahist a cosa serve: Farmacia Subito – caverject 20 mg prezzo

zineryt farmacia online se puede comprar viagra sin receta en farmacias fisicas en espaГ±a donde comprar amoxicilina sin receta

zopiclone sans ordonnance: Pharmacie Express – surgam sans ordonnance

prisma compresse 50 mg online: Farmacia Subito – geffer reflusso

sirop d’argousier antidepresseur sans ordonnance pharmacie cialis generique en pharmacie sans ordonnance

vitamine pharmacie sans ordonnance: aderma epitheliale – viagra sildГ©nafil

farmacia online preguntas: se puede comprar ibuprofeno generico sin receta – oximetro farmacia online

https://pharmacieexpress.com/# prix du viagra generique

goviril en pharmacie sans ordonnance generique viagra durex sensation

farmacia online cruz verde: farmacia san pablo online – letrozol se puede comprar sin receta

farmacia online mascarillas fp2: Confia Pharma – se pueden comprar medicamentos sin receta

farmacia online sibilla Confia Pharma farmacia francese omeopatica online

natalben supra farmacia online: alcohol online farmacia – farmacia online argentina envГos a todo el paГs

sildГ©nafil en ligne: Pharmacie Express – ordonnance 100%

locorten stomatologico: urixana bustine – delecit 600 prezzo

como comprar metilfenidato sin receta: comprar hidroferol sin receta – mounjaro se puede comprar sin receta

comprar victoza sin receta comprar mascarillas de farmacia online puedo comprar furosemida sin receta

compra online y recogida en farmacia: puedo comprar citalopram sin receta – comprar accutane sin receta

pharmacie verrue sans ordonnance: acheter cialis generique – valeriane pharmacie sans ordonnance

https://pharmacieexpress.com/# lycopodium clavatum 15ch effets secondaires

algix prezzo Farmacia Subito bivis 40/10

farmacia sirmione online: frequil principio attivo – augmentin 12 compresse prezzo

farmacia online 24h: Farmacia Subito – frequil 100

farmacia online andalucia se puede comprar viagra en farmacias sin receta en espaГ±a farmacia online mascarillas reutilizables

peut on acheter du viagra sans ordonnance dans une pharmacie: analyse d’urine sans ordonnance – arnica montana 7 ch

cialis a vendre Pharmacie Express prorhinel pipette

rivotril gocce: mycostatin colluttorio prezzo – biochetasi per intossicazione alimentare

ketoderm sans ordonnance en pharmacie: calcium pharmacie sans ordonnance – tadalafil 10 mg sans ordonnance

autotest covid farmacia online Confia Pharma farmacia online mataro

condylome traitement sans ordonnance pharmacie: mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance pour infection urinaire – pilule jasmine generique

silodosina 8 mg prezzo farmacia online lombardia quanto costa il brufen 600

mejor farmacia online sildenafilo: farmacia la plata online – farmacia compra online rosario

https://farmaciasubito.shop/# telefil 5 mg 28 compresse prezzo

http://pharmmex.com/# what can you buy at a mexican pharmacy

online medicine india: medicine online shopping – india pharmacy market outlook

Motilium: proscar pharmacy online – rx partners pharmacy

rx pharmacy india oakdell pharmacy sunday store hours medical pharmacy west

indian online pharmacy: drugs from india – get medicines from india

accurate rx pharmacy columbia mo: Levitra Soft – rx to go pharmacy league city

can i buy saxenda in mexico: drug stores online – ozempic mexico pharmacy

people pharmacy zocor cialis pharmacy india canadia online pharmacy

savon pharmacy: Pharm Express 24 – best online cialis pharmacy reviews

mexican pharmacy for cialis: Pharm Mex – mexican pharmacy hgh

india pharmacy market prescription drugs from india india pharmacy international shipping

canadian pharmacies that ship to the us: buy ozempic in mexico – can u order pain pills online

tesco pharmacy viagra cost: humana pharmacy login – legal online pharmacy percocet

buy medicine online india b pharmacy fees in india pharmacy online india

online pharmacy india: Fluoxetine – pharmacy cheap

top online pharmacy 247: Pharm Express 24 – ed pills online pharmacy

online medicine tablets shopping lamotrigine online pharmacy o reilly pharmacy artane

mexican pharmacy t3: on line pharmacy.com – mexican pharmacy steroids

buy online medicine: online india pharmacy – indian pharmacy

india pharmacy cialis: india pharmacy market – all day pharmacy india

ed pills online: envision rx pharmacy locator – buying viagra from pharmacy

avandia retail pharmacy: viagra overseas pharmacy – vips pharmacy viagra

online medicines india: InPharm24 – india e-pharmacy market size 2025

viagra pfizer online pharmacy Pharm Express 24 Artane

actos online pharmacy: Pharm Express 24 – proscar online pharmacy

https://inpharm24.com/# meds from india

pharmacy artane castle shopping centre Pharm Express 24 best online pharmacy to buy accutane

your rx pharmacy grapevine tx: Pharm Express 24 – Lamivudin (Cipla Ltd)

online india pharmacy reviews divya pharmacy india all day pharmacy india

list of pharmacies in india: india pharmacy ship to usa – indian pharmacy

meijer pharmacy free generic lipitor Pharm Express 24 pharmacy online coupon

https://pharmexpress24.shop/# omeprazole tesco pharmacy

sildenafil discount generic: 150 mg viagra online – buy viagra europe

viagra 400mg: VGR Sources – cheap viagra online united states

where can i buy female viagra in india buy viagra online usa no prescription lowest price for generic viagra

female viagra pills australia: VGR Sources – female viagra capsules in india

where can you get female viagra pills: VGR Sources – lowest price viagra 100mg

buy 90 sildenafil 100mg price VGR Sources viagra pill where to buy

https://vgrsources.com/# viagra 100 pill

compare viagra prices: viagra side effects – where to buy viagra uk

Preis von Viagra 50 mg: VGR Sources – generic viagra soft pills

order viagra online pharmacy buy generic viagra in us buy viagra online mexico

sildenafil no prescription free shipping: over the counter viagra substitute – best sildenafil coupon

https://vgrsources.com/# where can i buy viagra over the counter usa

can you buy viagra in canada: viagra medicine in india – female viagra uk pharmacy

can i buy viagra online in canada cost viagra canada viagra generic australia

prescription for viagra: VGR Sources – viagra india buy

where can i buy viagra online in canada: sildenafil 20 mg discount – viagra price in us

sildenafil 50mg for sale: buy generic viagra online paypal – viagra 100mg price canada

https://vgrsources.com/# cheap viagra 100

order viagra australia: where do you get viagra – viagra online without prescription usa

viagra generic 20 mg VGR Sources generic viagra from canada

cost of female viagra: order brand viagra – viagra 100mg price comparison

buy viagra express: buy viagra 100 – viagra 20

viagra cheapest prices buy viagra online australia paypal viagra medicine online in india

generic viagra uk: where can i get viagra uk – viagra for sale uk

https://vgrsources.com/# sildenafil 20 mg coupon

cheap viagra canadian pharmacy: VGR Sources – cheap viagra online

sildenafil citrate tablets VGR Sources how to order sildenafil from canada

online female viagra: viagra best buy india – sildenafil 25 mg coupon

can you buy viagra in canada: VGR Sources – viagra tablets canada

buy viagra over the counter in australia VGR Sources viagra usa over the counter

viagra 100mg price canada: can you buy viagra in mexico over the counter – generic viagra canada price

canada pharmacy online viagra prescription: VGR Sources – viagra capsules in india

https://vgrsources.com/# side effects of viagra

viagra tablets online: how do i get viagra – viagra pills generic brand

generic viagra online europe: sildenafil 100mg without a prescription – buy real viagra online uk

where to get female viagra uk: VGR Sources – cost of viagra in mexico

https://vgrsources.com/# cost of sildenafil 30 tablets

viagra 100 mg tablet price: VGR Sources – female viagra pill buy

sildenafil 90mg: viagra 200mg price – sildenafil online no prescription

can you order viagra from canada viagra medication cost generic viagra online pharmacy uk

buy viagra cheap australia: cheap sildenafil – viagra canada online price

sildenafil online europe: VGR Sources – can you buy viagra over the counter in mexico

cheap generic viagra 150 mg VGR Sources generic sildenafil online

viagra generic europe: can i buy viagra over the counter in canada – viagra 100mg canada

https://vgrsources.com/# where to buy sildenafil online

Rybelsus for blood sugar control: SemagluPharm – Order Rybelsus discreetly

SemagluPharm: Semaglu Pharm – Rybelsus 3mg 7mg 14mg

buy crestor CrestorPharm Crestor Pharm

Lipi Pharm: LipiPharm – Lipi Pharm

http://lipipharm.com/# Atorvastatin online pharmacy

prednisone nz: PredniPharm – buy prednisone 1 mg mexico

LipiPharm Atorvastatin online pharmacy Lipi Pharm

prednisone tablet 100 mg: prednisone generic cost – prednisone 20mg tab price

buy prednisone without a prescription best price PredniPharm PredniPharm

PredniPharm: PredniPharm – Predni Pharm

https://prednipharm.shop/# prednisone 20 mg tablets

LipiPharm: USA-based pharmacy Lipitor delivery – LipiPharm

Semaglu Pharm Semaglutide tablets without prescription Rybelsus 3mg 7mg 14mg

rybelsus 7 mg vs 14 mg weight loss: Semaglu Pharm – rybelsus price in usa

semaglutide precio: Semaglutide tablets without prescription – Semaglu Pharm

Lipi Pharm LipiPharm what can i take instead of lipitor

rybelsus,: Semaglu Pharm – Rybelsus side effects and dosage

LipiPharm: lipitor drug interactions – atorvastatin 40 mg price

USA-based pharmacy Lipitor delivery lipitor pregnancy category can lipitor cause dementia

Predni Pharm: Predni Pharm – buy prednisone without a prescription

Order cholesterol medication online Lipi Pharm No RX Lipitor online

how many possible stereoisomers are there for crestor: CrestorPharm – Safe online pharmacy for Crestor

https://semaglupharm.com/# Semaglu Pharm

what is the generic name of lipitor: will atorvastatin lower blood pressure – LipiPharm

CrestorPharm: Online statin therapy without RX – Affordable cholesterol-lowering pills

Crestor 10mg / 20mg / 40mg online: Crestor Pharm – Crestor Pharm

Predni Pharm prednisone purchase online Predni Pharm

http://semaglupharm.com/# Semaglu Pharm

SemagluPharm: п»їBuy Rybelsus online USA – Affordable Rybelsus price

https://prednipharm.com/# PredniPharm

him and hers semaglutide Semaglu Pharm Rybelsus side effects and dosage

п»їBuy Rybelsus online USA: Semaglu Pharm – Semaglu Pharm

CrestorPharm: CrestorPharm – Crestor Pharm

prednisone tablets india Predni Pharm Predni Pharm

order prednisone online no prescription: 54 prednisone – Predni Pharm

https://semaglupharm.com/# SemagluPharm

SemagluPharm: SemagluPharm – how much semaglutide to take

Semaglu Pharm what is in rybelsus SemagluPharm

Best price for Crestor online USA: Order rosuvastatin online legally – CrestorPharm

LipiPharm: Order cholesterol medication online – LipiPharm

Buy statins online discreet shipping: crestor for triglycerides – CrestorPharm

ozempic vs semaglutide Semaglu Pharm what does semaglutide do

where can i get prednisone over the counter: no prescription online prednisone – PredniPharm

http://prednipharm.com/# prednisone 20

Affordable cholesterol-lowering pills: CrestorPharm – Crestor Pharm

semaglutide reconstitution calculator: Semaglu Pharm – ozempic vs rybelsus vs wegovy

SemagluPharm is rybelsus covered by medicare SemagluPharm

No prescription diabetes meds online: rybelsus weight loss – semaglutide and constipation

LipiPharm: USA-based pharmacy Lipitor delivery – atorvastatin intensity

Lipi Pharm Lipi Pharm Lipi Pharm

https://lipipharm.shop/# plavix vs lipitor

Semaglu Pharm: SemagluPharm – Semaglu Pharm

what is the main side effect of atorvastatin: LipiPharm – pravastatin versus atorvastatin

Predni Pharm prednisone 20mg nz prednisone 50

Predni Pharm: prednisone buy no prescription – Predni Pharm

should you take lipitor at night: LipiPharm – Cheap Lipitor 10mg / 20mg / 40mg

Order Rybelsus discreetly Semaglu Pharm Semaglu Pharm

https://semaglupharm.com/# Semaglu Pharm

Crestor Pharm: CrestorPharm – Crestor Pharm

prednisone 20 mg: PredniPharm – prednisone pills for sale

prednisone 50 Predni Pharm PredniPharm

Crestor Pharm: Crestor Pharm – Buy statins online discreet shipping

can atorvastatin cause erectile dysfunction Lipi Pharm Lipi Pharm

https://semaglupharm.shop/# Affordable Rybelsus price

LipiPharm: LipiPharm – Lipi Pharm

Semaglu Pharm: semaglutide syringe – rybelsus class

Semaglu Pharm SemagluPharm Semaglu Pharm

CrestorPharm: rosuvastatin warnings – crestor leg pain

Semaglu Pharm: Online pharmacy Rybelsus – rybelsus precio farmacia guadalajara

Rybelsus 3mg 7mg 14mg rybelsus 14 mg coupon Order Rybelsus discreetly

PredniPharm: Predni Pharm – prednisone 10mg prices

https://crestorpharm.com/# CrestorPharm

atorvastatin good rx: USA-based pharmacy Lipitor delivery – USA-based pharmacy Lipitor delivery

PredniPharm PredniPharm iv prednisone

Crestor Pharm: Crestor home delivery USA – CrestorPharm

PredniPharm: iv prednisone – order prednisone online no prescription

steroids prednisone for sale prednisone otc uk Predni Pharm

Lipi Pharm: LipiPharm – Cheap Lipitor 10mg / 20mg / 40mg

PredniPharm: prednisone 20 mg pill – prednisone 40 mg price

atorvastatin what is it used for how much is lipitor without insurance lipitor for

buy medicines online in india: India Pharm Global – India Pharm Global

canadian pharmacy india: Canada Pharm Global – best mail order pharmacy canada

India Pharm Global best india pharmacy India Pharm Global

canada rx pharmacy world: www canadianonlinepharmacy – canadian pharmacy 24 com

https://canadapharmglobal.shop/# canadian discount pharmacy

best canadian online pharmacy: reliable canadian pharmacy – best canadian pharmacy online

India Pharm Global п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india indianpharmacy com

canadian mail order pharmacy: canada pharmacy – canadian pharmacy 1 internet online drugstore

buy prescription drugs from india: India Pharm Global – India Pharm Global

http://indiapharmglobal.com/# India Pharm Global

India Pharm Global India Pharm Global best india pharmacy

https://medsfrommexico.shop/# Meds From Mexico

medication from mexico pharmacy: Meds From Mexico – Meds From Mexico

canada pharmacy world: canadianpharmacymeds – best mail order pharmacy canada

pharmacy rx world canada Canada Pharm Global canadian pharmacy uk delivery

canadian family pharmacy: Canada Pharm Global – canadian pharmacy ltd

legit canadian pharmacy online: canadian pharmacy – is canadian pharmacy legit

India Pharm Global buy medicines online in india buy prescription drugs from india

https://canadapharmglobal.com/# buying drugs from canada

purple pharmacy mexico price list: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – buying from online mexican pharmacy

pharmacy wholesalers canada: best rated canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy world reviews

best india pharmacy: online shopping pharmacy india – buy prescription drugs from india

indian pharmacy paypal India Pharm Global Online medicine home delivery

https://medsfrommexico.com/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

top 10 pharmacies in india: India Pharm Global – India Pharm Global

https://raskapotek.shop/# Rask Apotek

EFarmaciaIt: onaka fiale a cosa serve – bentelan farmaco da banco

Papa Farma: Papa Farma – comprar farmacia

micostatin canarios Papa Farma viternum espaГ±a

EFarmaciaIt: dr max opinioni – farmacie on line affidabili

las mejores farmacias online: dodot sensitive talla 1 oferta – Papa Farma

Papa Farma Papa Farma Papa Farma

https://papafarma.shop/# Papa Farma

foglio illustrativo brufen 600: EFarmaciaIt – EFarmaciaIt

Svenska Pharma Svenska Pharma snabb hemleverans apotek

dusjsГҐpe apotek: fotsopp apotek – Rask Apotek

EFarmaciaIt: slinda anticoncezionale – ryaltris spray costo

https://svenskapharma.shop/# lasarett apotek

Svenska Pharma: Svenska Pharma – naturlig avmaskning hГ¤st

Svenska Pharma Svenska Pharma Svenska Pharma

farmacias abiertas hoy vigo: frmacia – Papa Farma

Rask Apotek: doppler apotek – fjerne Гёrevoks apotek

EFarmaciaIt farmcia online inatal duo a cosa serve

https://raskapotek.shop/# antacida apotek

EFarmaciaIt: EFarmaciaIt – EFarmaciaIt

pink eye svenska: Svenska Pharma – kГ¶pa potensmedel pГҐ nГ¤tet

farmacia abierta alicante celestone embarazo Papa Farma

Svenska Pharma: Svenska Pharma – Svenska Pharma

EFarmaciaIt: EFarmaciaIt – deursil 50 mg

EFarmaciaIt sirdalud compresse 4 mg prezzo EFarmaciaIt

http://svenskapharma.com/# african black soap apotek

de la farmacia: dos pharma – compra de medicamentos online

EFarmaciaIt EFarmaciaIt EFarmaciaIt

Svenska Pharma: apotek shampoo – recept hemleverans

farmcaia misoprostol comprar Papa Farma

Svenska Pharma: Svenska Pharma – Svenska Pharma

enterogermina quanto costa EFarmaciaIt EFarmaciaIt

Papa Farma: Papa Farma – Papa Farma

http://efarmaciait.com/# EFarmaciaIt

http://pharmajetzt.com/# shop apotheke versandapotheke versandkostenfrei

pharmagarde 59: l’ordre national des pharmaciens – Pharma Confiance

PharmaConnectUSA: PharmaConnectUSA – PharmaConnectUSA

do pharmacy sell viagra depo provera pharmacy Pharma Connect USA

tesco pharmacy lariam PharmaConnectUSA Pharma Connect USA

tylenol 1 pharmacy: pharmacy ce online – Pharma Connect USA

http://pharmajetzt.com/# Pharma Jetzt

PharmaConnectUSA Pharma Connect USA Pharma Connect USA

arrГЄter la drogue du jour au lendemain: Pharma Confiance – Pharma Confiance

Medicijn Punt inloggen apotheek online apotheek

Pharma Confiance: grande pharmacie autour de moi – Pharma Confiance

Pharma Connect USA: best australian online pharmacy – PharmaConnectUSA

https://medicijnpunt.shop/# Medicijn Punt

apotheke online gГјnstig bestellen: Pharma Jetzt – apohteke

pharmacie en ligne sans frais de port livre homeopathie parapharmacie la moins chГЁre paris

propecia pharmacy prices scripts rx pharmacy PharmaConnectUSA

internet apotheken ohne versandkosten: pille danach apotheke online – Pharma Jetzt

online apotheke versandkostenfrei: medikamente preisvergleich testsieger – PharmaJetzt

apotheke ohne versandkosten Pharma Jetzt versandkostenfreie apotheke

apotheke bestellen schnell: PharmaJetzt – Pharma Jetzt

https://medicijnpunt.com/# MedicijnPunt

MedicijnPunt: Medicijn Punt – apotheek producten

http://pharmajetzt.com/# Pharma Jetzt

Pharma Confiance Pharma Confiance Pharma Confiance

shoop apotheke: apotheke versand – online-apotheken

MedicijnPunt: MedicijnPunt – medicijnen kopen

PharmaJetzt: PharmaJetzt – lavita login

Medicijn Punt bestellen apotheek MedicijnPunt

http://pharmaconfiance.com/# Pharma Confiance

bestellapotheken: apotheke in deutschland – PharmaJetzt

PharmaConnectUSA Pharma Connect USA Pharma Connect USA

medis medikamente: gГјnstigste online apotheke – apotheke online gГјnstig

online apotheke germany: beste online apotheke – gГјnstige online apotheke

http://pharmaconfiance.com/# acheter nexgard moins cher

PharmaConnectUSA: legit online pharmacy – tamiflu which pharmacy has the best deal

recept medicijn: MedicijnPunt – online apotheek nederland

recept medicijnen Medicijn Punt Medicijn Punt

Pharma Connect USA: usa pharmacy – cefixime online pharmacy

Pharma Confiance: Pharma Confiance – pharmacie chateauneuf sur cher

wholesale pharmacy order viagra from mexican pharmacy pharmacy online coupon

https://pharmaconnectusa.shop/# online pharmacy store hyderabad

Pharma Jetzt: apotheke internet – Pharma Jetzt

Medicijn Punt: MedicijnPunt – online apotheek nederland

online pharmacy weight loss PharmaConnectUSA hair loss

Pharma Connect USA: PharmaConnectUSA – Pharma Connect USA

Pharma Jetzt: apotheje online – PharmaJetzt

Medicijn Punt farma online Medicijn Punt

PharmaConnectUSA best pharmacy to buy provigil flovent online pharmacy

online medicijnen: Medicijn Punt – medicijn

Pharma Confiance: amoxicilline humain pour chien – commande dd

http://pharmajetzt.com/# versandkostenfreie apotheke

des pharmacie Pharma Confiance Pharma Confiance

http://pharmaconfiance.com/# Pharma Confiance

MedicijnPunt: apotheke online – medicijnen op recept online bestellen

asacol online pharmacy Pharma Connect USA Pharma Connect USA

http://pharmajetzt.com/# Pharma Jetzt

cialis prix france: Pharma Confiance – gode 6 cm

Pharma Jetzt wegovy online apotheke Pharma Jetzt

beste online apotheke: PharmaJetzt – medikamente sofort liefern

online medicijnen kopen: Medicijn Punt – Medicijn Punt

constipation homГ©opathie adulte: Pharma Confiance – parapharmacie caen centre ville

pharmacie vichy Pharma Confiance Pharma Confiance

pharmacie espagnole en ligne: meilleure crГЁme visage 60 millions consommateur – Pharma Confiance

https://pharmaconnectusa.com/# Pharma Connect USA

PharmaJetzt: apotal apotheke online bestellen – PharmaJetzt

MedicijnPunt: online apotheek – gratis verzending – europese apotheek

online apotheke auf rechnung luitpoldapotheke bad steben PharmaJetzt

Medicijn Punt: medicijnlijst apotheek – medicatie aanvragen

https://pharmaconfiance.com/# bienfait des chats selon leur couleur

MedicijnPunt: inloggen apotheek – Medicijn Punt

https://pharmaconfiance.com/# Pharma Confiance

the people’s pharmacy wellbutrin pharmacy rx solutions rx pharmacy india

parapharmacie odeon: Pharma Confiance – montre menthe Г l’eau

medizin bestellen: PharmaJetzt – PharmaJetzt

https://pharmajetzt.shop/# Pharma Jetzt

online pharmacy no prescription zoloft: express scripts pharmacy – dominican republic pharmacy online

Pharma Connect USA: Pharma Connect USA – PharmaConnectUSA

http://pharmajetzt.com/# Pharma Jetzt

gss luxembourg: parapharmacie ou pharmacie – Pharma Confiance

online medicijnen bestellen: medicijnen online kopen – MedicijnPunt

Pharma Confiance: Pharma Confiance – para sante service

PharmaConnectUSA: target pharmacy viagra – PharmaConnectUSA

apotheken produkte: medikamente preisvergleich – PharmaJetzt

Pharma Jetzt: apotheke im internet – apotal apotheke online shop bestellen

https://pharmajetzt.shop/# apotheke venlo

https://pharmaconfiance.com/# creme metronidazole

Pharma Confiance: pharmacie proche d’ici – pharmacie d

Pharma Connect USA: cialis online pharmacy reviews – Pharma Connect USA

upsa commande: normandie pionniГЁres – Pharma Confiance

PharmaJetzt welches ist die gГјnstigste online apotheke shop aphotheke

https://medicijnpunt.shop/# medicatie apotheker

Pharma Confiance: Pharma Confiance – Pharma Confiance

priligy uk pharmacy: ramipril online pharmacy – Pharma Connect USA

Pharma Confiance pharmacie du grand large Pharma Confiance

PharmaConnectUSA: PharmaConnectUSA – PharmaConnectUSA

tabletten bestellen: PharmaJetzt – Pharma Jetzt

PharmaConnectUSA: Pharma Connect USA – unc student store pharmacy

online apoteken: liefer apotheke – Pharma Jetzt

https://pharmajetzt.com/# luitpold apotheke selbitz

snel medicijnen bestellen apotheke online medicijnen bestellen zonder recept

canadian neighbor pharmacy: canadian compounding pharmacy – canadadrugpharmacy com

online shopping pharmacy india: buy medicines online in india – india online pharmacy

mexican rx online mexican pharmaceuticals online purple pharmacy mexico price list

IndiMeds Direct: IndiMeds Direct – IndiMeds Direct

https://indimedsdirect.shop/# IndiMeds Direct

medication canadian pharmacy: cross border pharmacy canada – canadian discount pharmacy

IndiMeds Direct indian pharmacies safe india pharmacy

IndiMeds Direct: online shopping pharmacy india – india pharmacy

canadian pharmacy com CanRx Direct certified canadian pharmacy

IndiMeds Direct: IndiMeds Direct – india pharmacy

https://indimedsdirect.shop/# best online pharmacy india

reputable indian online pharmacy: IndiMeds Direct – IndiMeds Direct

canadian pharmacy cheap my canadian pharmacy rx canadian family pharmacy

Online medicine home delivery: IndiMeds Direct – IndiMeds Direct

IndiMeds Direct cheapest online pharmacy india IndiMeds Direct

https://canrxdirect.shop/# adderall canadian pharmacy

best canadian online pharmacy: CanRx Direct – canadian pharmacy meds review

canadianpharmacyworld com CanRx Direct canadian discount pharmacy

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: TijuanaMeds – best online pharmacies in mexico

TijuanaMeds: TijuanaMeds – TijuanaMeds

TijuanaMeds mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs TijuanaMeds

Add Your Comment